The epidemiology of Mpox (previously Monkeypox) continues to evolve with a new outbreak being caused by a different “strain”. Since 2022, person-to-person transmission of Mpox has been sustained in a global outbreak, primarily among men who have sex with men (MSM). The stigma associated with this disease has negatively impacted containment of this virus with only 1 in 4 at-risk persons being immunized.1 Mpox continues to circulate in the U.S. and modeling data suggest that if vaccine coverage does not increase, large outbreaks could be expected in the future.2 This would most certainly result in a percentage of these patients being hospitalized with risk of transmission within the hospitals walls.

About MPox Clades

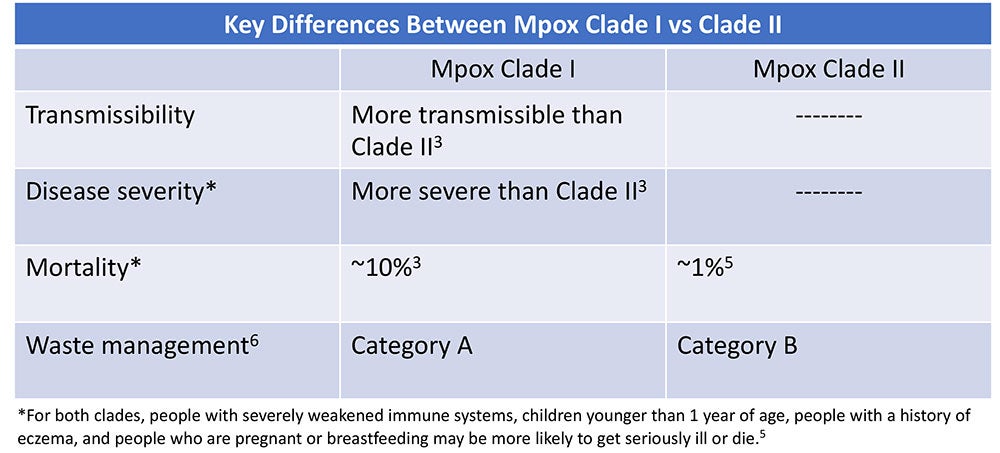

Clades are groups of genetically linked viruses. Mpox consists of two clades: Mpox Clade II which causes less severe disease and Mpox Clade I which is more transmissible and causes more severe disease with a mortality rate as high as 10%.3 In early December 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a health advisory of a sexually-transmitted Mpox Clade I outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).1 Clinicians were alerted to the possibility of Mpox Clade I in travelers who have been in the DRC. To date, no Mpox Clade I cases have been identified in the U.S., however the World Health Organization (WHO) states there is moderate risk of Mpox Clade I further spreading to worldwide.1,4

What Healthcare Professionals Should Know

The good news is that treatment and prevention measures are the same for both Mpox clades.3 At-risk persons should get vaccinated and should seek medical attention if they have symptoms.3 The virus can be spread from person-to-person from contact with Mpox lesions or respiratory secretions and droplets or from contact with contaminated materials, including soft surfaces like bedding or clothing.3 Because Mpox is spread by direct contact, frequent hand hygiene and routine cleaning and disinfection of environmental surfaces is crucial.3,7 Disinfectants for emerging viral pathogens from the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) List Q should be used.8 The EPA has extended the use for List Q disinfectants for mpox through May 2025.9 Learn more here about navigating List Q as it relates to Mpox.

The risk for occupational transmission of Mpox Clade II to healthcare workers (HCWs) is considered to be low — in fact, only a few cases have been reported.10 However, Mpox Clade I is more transmissible so its plausible that the risk to HCWs may be higher. To protect themselves, HCWs should do the following:

- Adhere to standard and transmission-based precautions, including appropriate PPE.7

- Perform frequent hand hygiene.

- Frequently clean and disinfect high-touch surfaces in mpox patient rooms.

- Avoid dry dusting, sweeping, or vacuuming which can aerosolize the virus.7

- Perform aerosol-generating procedures in a negative pressure room.7

- Never shake or handle soiled linens in a manner that may disperse infectious material.7

- Handle waste in accordance with federal, state, and local regulations. Mpox Clade I is Category A Waste, while Mpox Clade II is Category B Waste.6

The epidemiology of mpox continues to evolve with a substantial increase in the more pathogenic strain of mpox (Clade I) in the DRC.1 Healthcare workers should continue to be vigilant and consider mpox when evaluating the cause of rashes.1 For more information, see our Mpox Pathogen Education Sheet.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). HAN Alert: Mpox Caused by Human-to-Human Transmission of Monkeypox Virus with Geographic Spread in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Dec 7, 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2023/han00501.asp

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mpox Updates for Clinicians, Dec 20, 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/dear_colleague/2023/dcl-122023-mpox-updates.html

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox: What we know; Dec 1, 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://www.who.int/multi-media/details/mpox-what-we-know

4. World Health Organization (WHO). Multi-country outbreak of mpox; Dec 22, 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/multi-country-outbreak-of-mpox--external-situation-report-31---22-december-2023

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). About Mpox [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/about/index.html

6. U.S. Department of Transportation. Transporting Infectious Substances Overview [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jan 1]. Available from https://www.phmsa.dot.gov/transporting-infectious-substances/transporting-infectious-substances-overview

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Mpox: Infection Prevention and Control of Mpox in Healthcare Settings [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/mpox/clinicians/infection-control-healthcare.html#anchor_1653508940308

8. US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Selected EPA-Registered Disinfectants [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/selected-epa-registered-disinfectants

9. US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Emerging Viral Pathogen Guidance and Status for Antimicrobial Pesticides [Internet]. [cited 2023 Dec 31]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/emerging-viral-pathogen-guidance-and-status-antimicrobial-pesticides

10. Alarcón J, Kim M, Balanji N, Davis A, Mata F, Karan A, et al. Occupational Monkeypox Virus Transmission to Healthcare Worker, California, USA, 2022. Emerg Infect Dis. 2023;29(2):435-437. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2902.221750

The 21st century world is being impacted by emerging pathogens on an unprecedented scale.¹ Not only are we experiencing diagnostic and treatment challenges that come with emerging pathogens, but there can also be implications for cleaning and disinfecting against a novel pathogen.

Where to start?

It is imperative to select appropriate disinfecting products when dealing with emerging pathogens. But when a pathogen is novel, it is not likely that a disinfectant on the market will have claims against it — at least not right away — and adding new claims to an existing product does not happen overnight. It takes about a year to get new claims approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

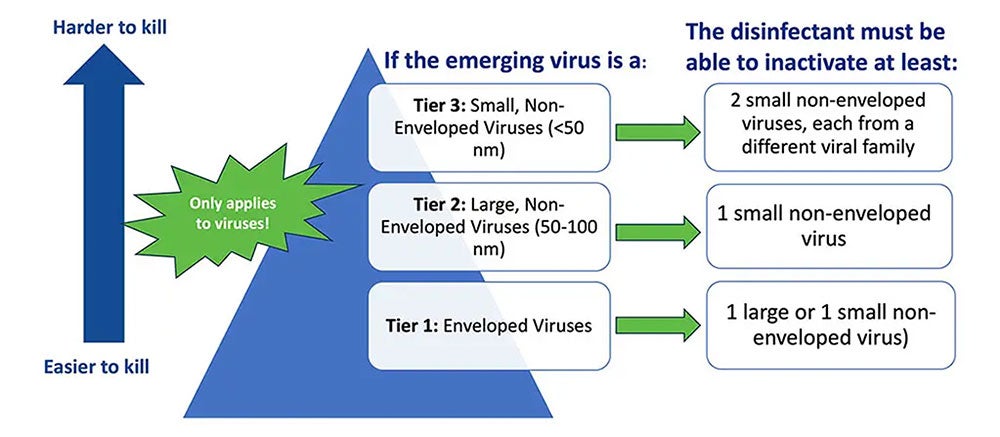

So, how do you identify an effective product? The first step is to see if any specific policies, requirements, or resources have been issued in relation to the novel pathogen(s) in question. For example, the EPA's Emerging Viral Pathogen Policy and (e.g., List N, List K, List Q) can be used to find appropriate products (Image 1). It is important to note that the EPA’s Emerging Viral Pathogen policy only applies to viruses. It does not apply to emerging bacteria, fungi, or other pathogens.

Understanding EPA’s List Q

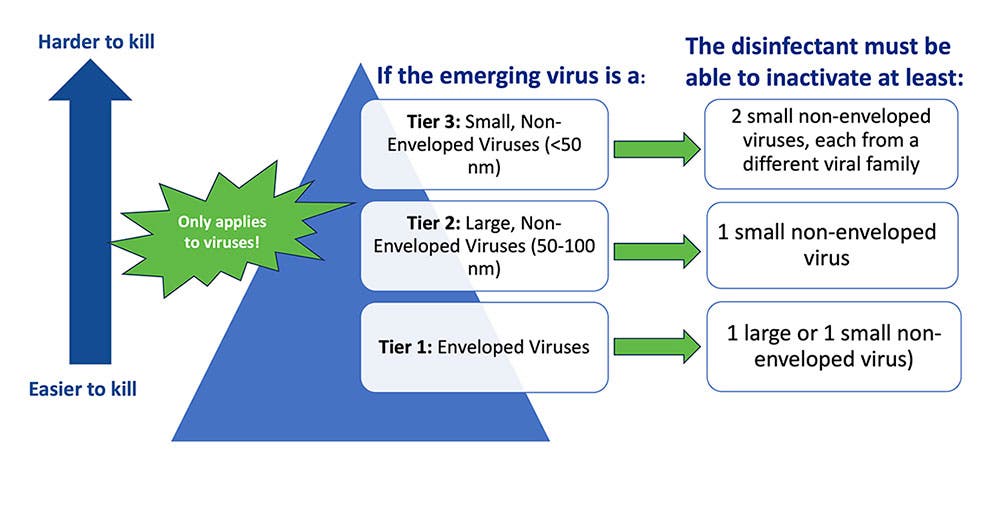

List Q is unique from the other EPA Lists because it does not target a specific pathogen. With this List, the user searches for eligible products for use against an emerging pathogen by selecting the appropriate tier based on virus type.

To navigate List Q, there are a few things you need to know about the emerging pathogen including if it is:

- An enveloped virus (tier 1- the easiest of the 3 types to kill),

- A large non-enveloped virus (tier 2), or a

- A small non-enveloped virus (tier 3 – the hardest of the virus types to kill).

Lastly, it is important to understand that because a given product from List Q meets the criteria for use against one emerging virus (e.g., Mpox), it does not mean this product will be effective against any future emerging viruses. It is designed to be used on a pathogen-by-pathogen basis.2

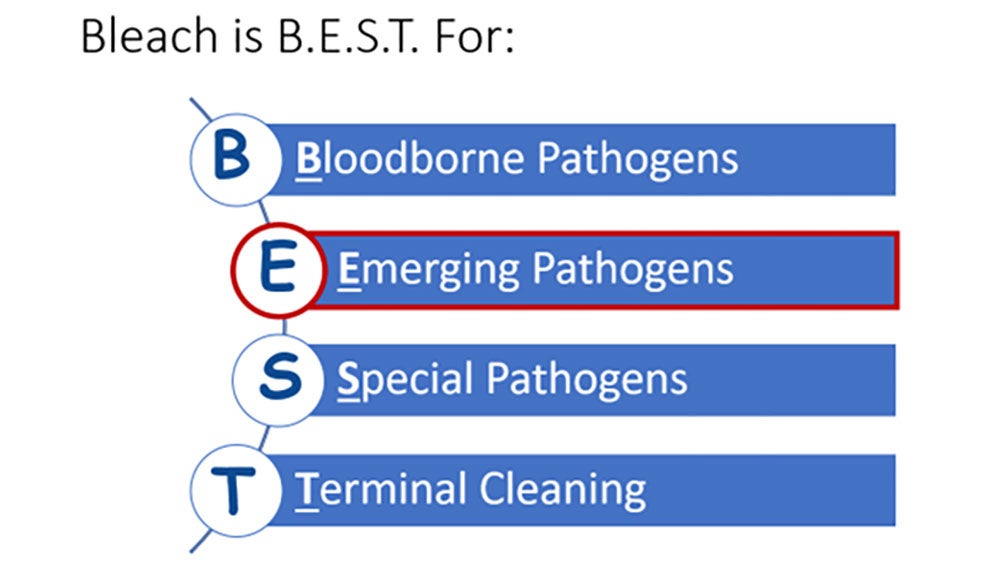

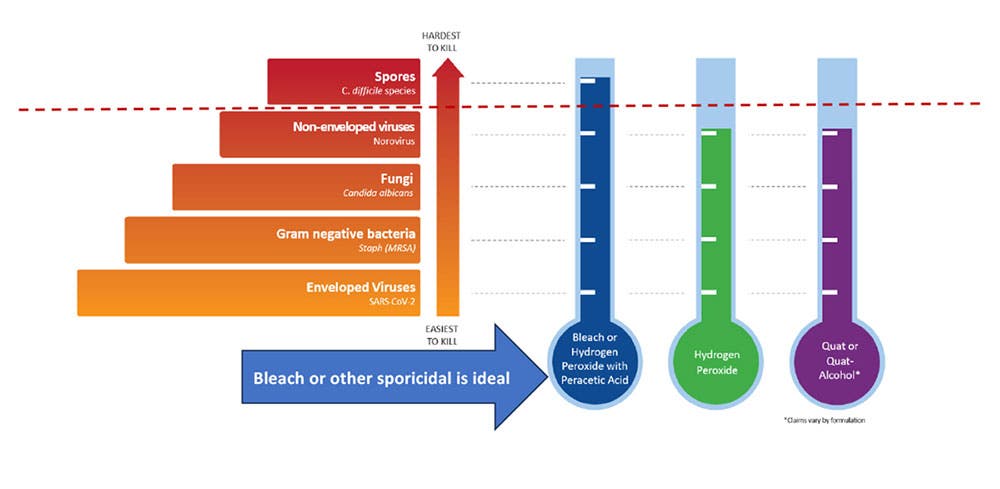

In situations when guidance like the EPAs Emerging Viral Pathogen policy is not activated, I recommend using a sporicidal, like bleach, because it is broad-spectrum against hard-to-kill pathogens (see CloroxPro “Bleach is B.E.S.T.” blog). Please note — some disinfecting chemistries may be more effective than others against a given pathogen. For example, disinfectants with quaternary ammonium compounds (e.g., “quats”) as the only active ingredient have not been found to be effective against Candida auris.3

Control and contain

Beyond identifying the correct product to use, it is also imperative to identify a process for managing an emerging pathogen. For example, protocols should include the personal protective equipment (PPE) to be worn to enter the room, cleaning frequency, and the appropriate disinfectant to be used. Cleaning and disinfecting protocols may differ by pathogen, so it is also important that staff are educated and trained to safely and effectively clean and disinfect against novel pathogens.

Additional Resources

In addition to the EPA's Emerging Viral Pathogen Policy and the EPA Disinfectant Lists, other organizations have published helpful resources you can use to help you identify the appropriate disinfecting products to use and implement a process for managing an emerging pathogen. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance, the National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center (NETEC) is another great resource for guidelines. You can also check out the CloroxPro HealthyClean® online learning platform for more training and education opportunities for yourself or your staff.

References

1. Ambat A, Vyas N. Assessment and preparedness against emerging infectious disease among private hospitals in a district of South India. Open Access: Med J Armed Forces India [internet]. 2022;78(1):42-46.

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. Disinfectants for Emerging Viral Pathogens (EVPs): List Q [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/disinfectants-emerging-viral-pathogens-evps-list-q

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Prevention and Control for Candida auris [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-infection-control.html

There is a silent public health threat more deadly than COVID-19 killing an estimated 6.2 million people each year across the globe.1 For perspective, COVID-19 killed 6.9 million people globally…but over a 3-year period!2 The threat: antimicrobial resistance (AMR). The challenge with AMR pathogens is that they are not killed by the antimicrobial drugs typically used to treat them.3 AMR is now the third leading cause of death worldwide and is poised to rival the annual all-cancer death toll by the year 2050 with an estimated 10 million deaths.1,4

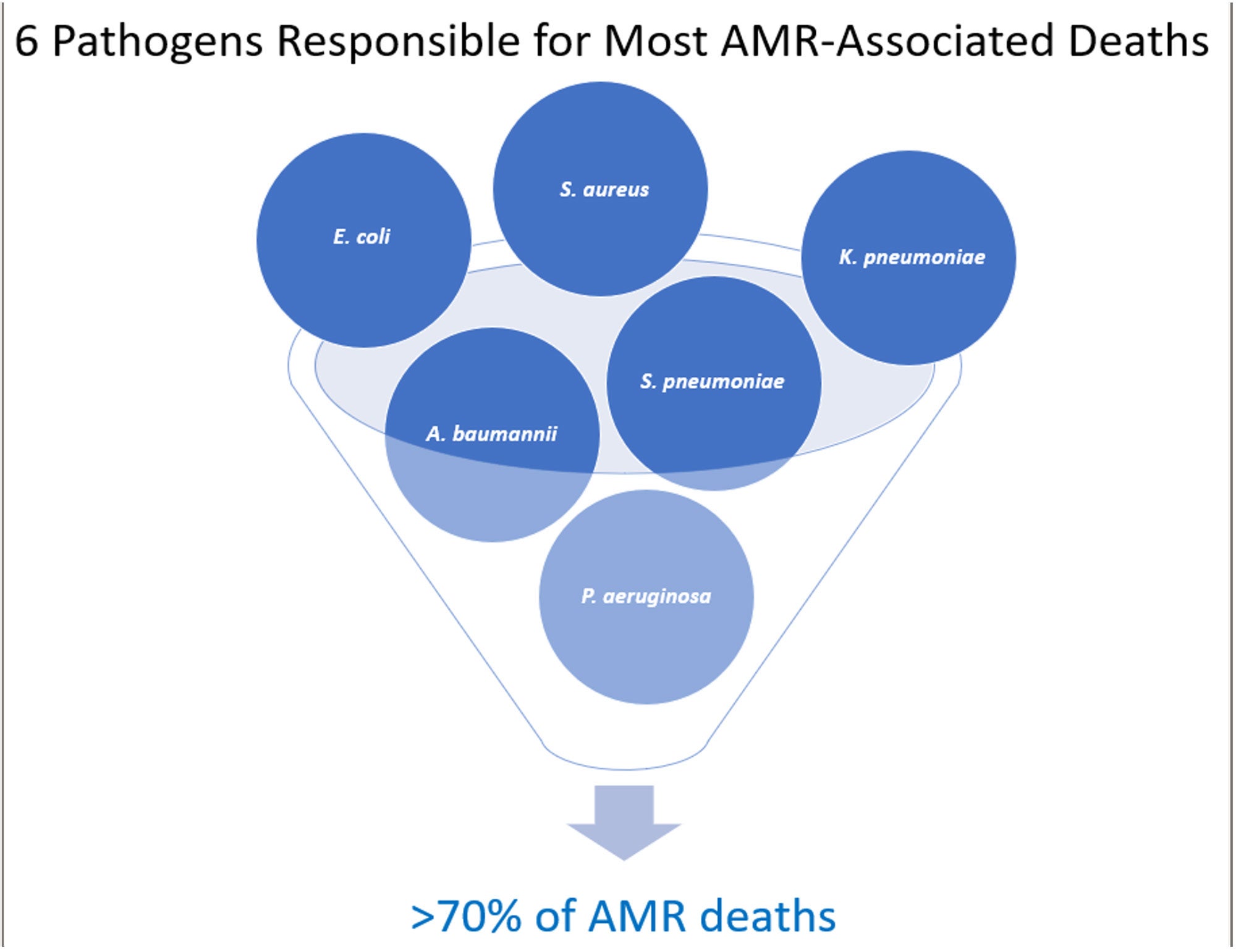

AMR is often referred to as the “Silent Pandemic” because it represents a slow and hidden threat that has the potential to cause widespread health consequences.5 With AMR continuously increasing and fewer new treatments in development, many experts believe that we are not entering, but rather we are living in the post-antimicrobial era.6 Surprisingly, only 6 pathogens are responsible for most of these infections.1

AMR Is Not a U.S. Problem — or Is It?

More than 3 million Americans acquire an AMR infection each year.7 While not in the top 6, Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) is also considered to be an AMR pathogen because it is associated with taking antibiotics. C. diff causes close to 50,000 U.S. deaths annually.8

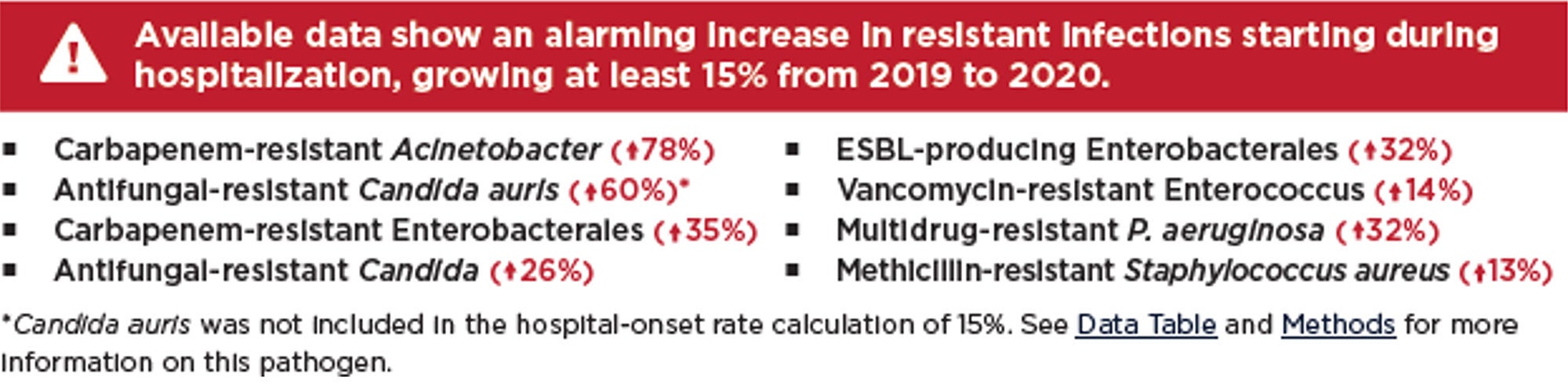

AMR was an issue before the pandemic, but pandemic-related factors have only intensified the problem including increased use of antibiotics as well as a healthcare system that was stressed to its limits. This made compliance with infection prevention and control measures more challenging8. There were also severe staffing shortages during this time which could have resulted in cutting corners. Replacement staff may not have been adequately trained in proper procedures. The result has been a significant increase in AMR with deaths increasing by 15% in just the first year of the pandemic.8

With the COVID-19 public health emergency declared over, our attention has been turned to other emerging and re-emerging microbial threats like Candida auris, Mpox, seasonal respiratory viruses, and even vaccine-preventable diseases. But if the future effectiveness of antimicrobial agents is to be preserved, it is imperative that AMR is given the same focused attention as the afore-mentioned pathogens. Recognized each year in November, World Antimicrobial Resistance Awareness Week (WAAW), is a campaign intended to do just that.9 This blog hopes to help WAAW in raising awareness of AMR and to promote the importance of a sanitary healthcare environment.

Slowing the Rate of AMR

WAAW’s theme this year is “Preventing antimicrobial resistance together.”8 The causes of AMR are complex due to the interconnectivity between people, animals, and the environment (learn more at CDC’s One Health). A multimodal approach, in which everyone plays a role, is crucial to slowing the rate of AMR and preserving antibiotics for future generations.

Key actions that the healthcare community can take to reduce AMR include:

- Perform pathogen surveillance for resistance patterns.

- Establish robust antimicrobial stewardship programs.

- Encourage immunizations of patients and staff.

- Perform frequent hand hygiene.

- Educate and train all healthcare staff on IPC measures to stop AMR spread.

- Ensure effective environmental cleaning and disinfection.

- Ensure cleaning and disinfection of medical equipment between patients.

The Relationship Between AMR and Environmental Cleaning & Disinfection

According to hygiene expert Dr. Nico Mutters, there are 3 reasons that AMR is increasing10:

- Selection due to improper antimicrobial use.

- Transmission resulting from inadequate IPC and hygiene (hands and environmental cleaning).

- Host factors.

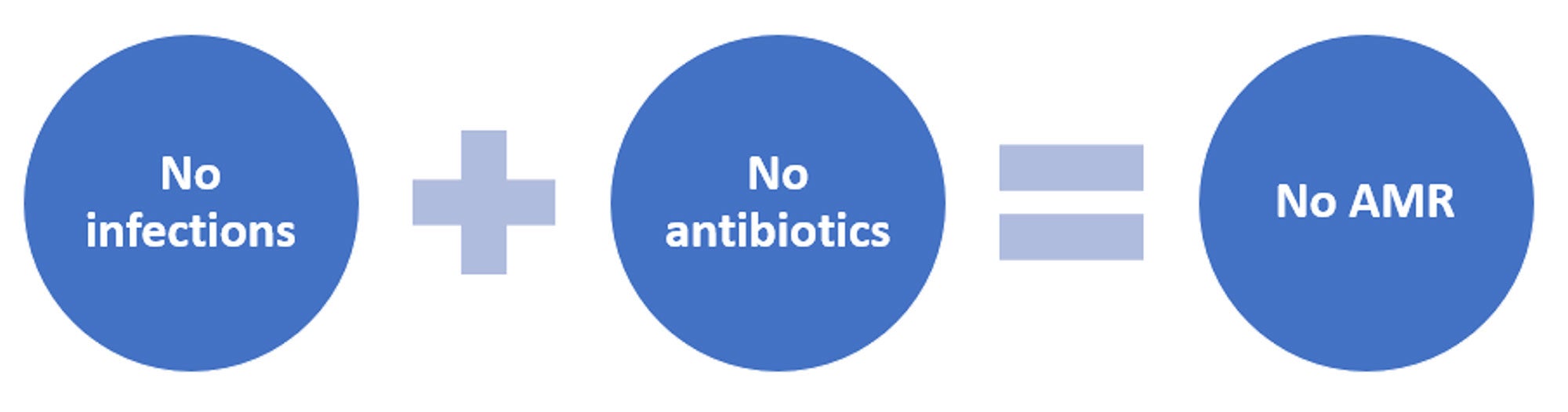

Studies show that more than 74% of healthcare surfaces are contaminated with AMR pathogens and that more than 50% of these surfaces that should be cleaned are missed.11,12,13 There is considerable evidence that environmental surface contamination plays a key role in the transmission of many pathogens, particularly those that are AMR. There is sufficient evidence to show that the next patient to be admitted to a room where the prior occupant harbored an AMR pathogen has up to a 3-fold increased risk for acquiring that pathogen.14 This is almost certainly due to inadequate cleaning and disinfection. Environmental cleaning and disinfection breaks the chain of infection by preventing transmission from contaminated environmental surfaces. By preventing infections, the need for antibiotics is reduced, thereby decreasing the risk resistance. A clean and sanitary environment also reduces the direct transmission of AMR pathogens between patients.

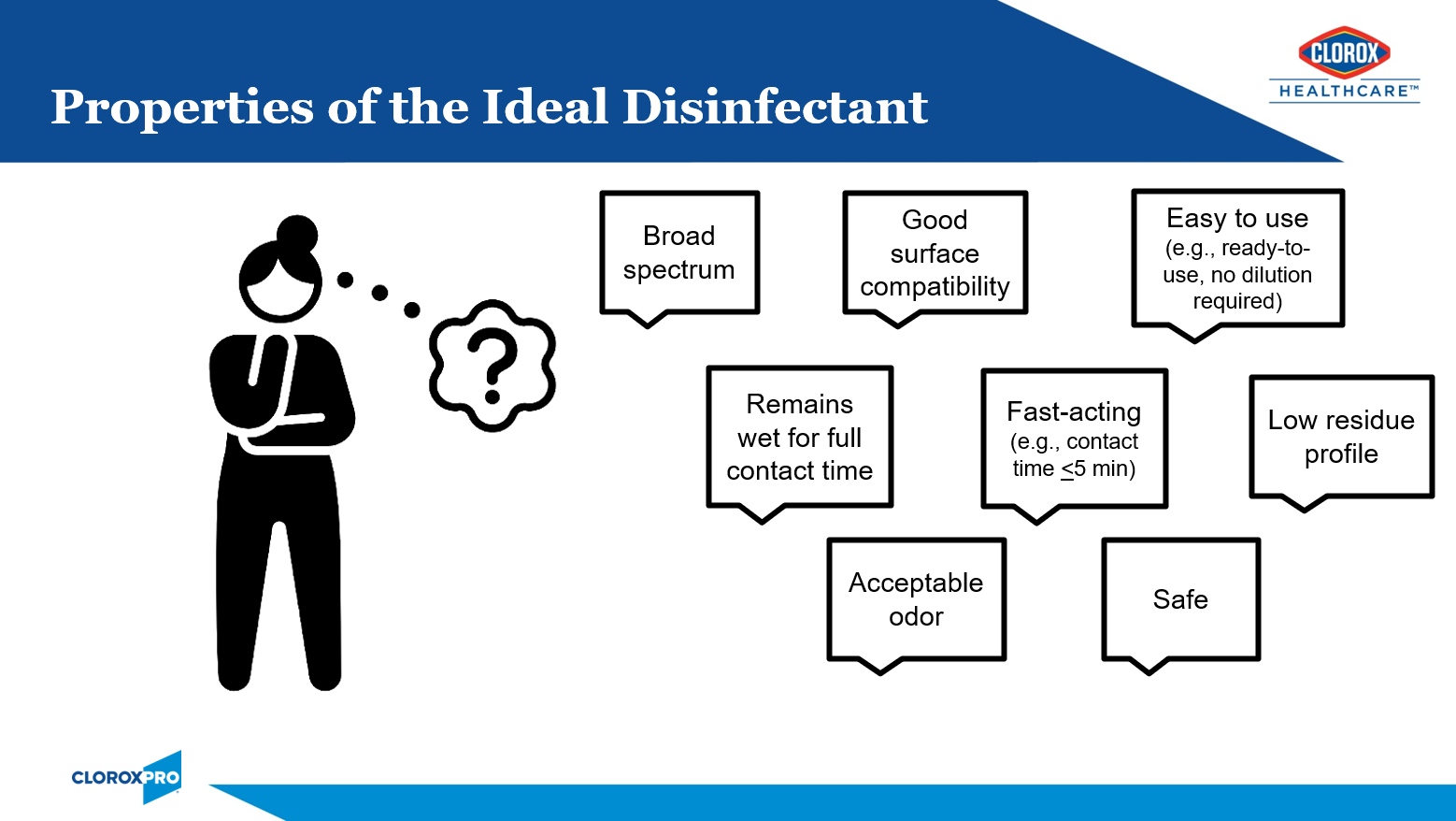

To combat AMR, I recommend selecting products that target pathogens of concern for the facility and that meet the users desired properties of the ideal disinfectant. Sporicidal disinfectants (e.g., bleach), with its broad antimicrobial activity, are ideal for combatting AMR. I also recommend using a sporicidal disinfectant for all discharge and terminal room cleans. This helps to ensure the highest level of cleanliness for the next patient admitted to that room.

Conclusion

The rates of AMR have only worsened in recent years and treatment options are becoming more limited. AMR infections come with high consequences including increased lengths of stay, increased cost, and can even result in loss of life. The time for action to reverse this trend is NOW. Learn more here.

References

1. Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Open Access Lancet [Internet]. 2022; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0.

2. Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 28]. Available from: https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 02]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/narms/resources/glossary.html

4. United Nations. UN News: Reduce Pollution to combat ‘superbugs’ and other antimicrobial resistance [Internet]. [cited 2023 Nov 02]. Available from https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/02/1133227#:~:text=Overall%2C%20nearly%20five%20million%20deaths,globally%20by%20cancer%20in%202020.

5. Google Scholar. Search term “Silent Pandemic” [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 29]. Available from: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=silent+pandemic&btnG=

6. European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. Press Release ECCMID 2023, Copenhagen, 15-18 April [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 29]. Available from: https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/982758

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 Special Report: COVID-19 U.S. Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 30]. Available from: CDC.

9. World Health Organization. World AMR Awareness Week 2023 [Internet]. [cited 2023 Oct 28]. Available from: WHO.

10. Mutters, N. Proceedings from International Conference on Prevention & Control (ICPIC) 2023. Session: Are we prepared for future challenges in infection prevention and control?

11. Carling PC, Bartley JM. Evaluating hygienic cleaning in health care settings: what you do not know can harm your patients. AM J Infect Control. 2010;38:S41-50

12. McKinnell J, Miller L, Singh R, Walters D, Peterson E, Huang S. High Prevalence of MDRO Colonization in 28 NHs: An Iceberg Effect. JAMDA. 2020;21(12):1937-1943

13. Cassone M, Wang J, Lansing B, Mantey J, Gibson K, Gontjes K, et al. Proceedings from SHEA 2022. Poster: Diversity and persistence of MRSA and VRE in NHs: Environmental screening and whole-genome sequencing. ASHE. 2022;2:s80.

14. Chemaly R, Simmons S, Dale C, Ghantoji S, Rodriguez M, Gubb J, et al. The role of the healthcare environment in the spread of MDROs: update on current best practices. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2014;2(3-4), 79-90.

Have you ever wondered what infection prevention and control (IPC) “looks like” in other parts of the world, and how our challenges compare? In the U.S., most Infection Preventionists (IPs) are budgeted to attend at least one conference per year, and international conferences are typically not within the budget. At least, this was the case when I worked in hospitals. After 24 years as an IP, my dream finally came true! I am eternally grateful to Clorox Healthcare for sending me to the International Consortium on Prevention and Infection Control (ICPIC) in Geneva, Switzerland this September. This blog is dedicated to honor Clean Hospitals Day, celebrated each year on October 20th, to raise awareness and foster engagement among healthcare facilities around the world on the important role of environmental hygiene in IPC.

ICPIC is a unique forum for the exchange of knowledge and experience in the prevention of healthcare associated infections (HAIs) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR). It also happens to be the largest IPC conference in Europe. The 1200+ participants, who traveled from across the globe, were stimulated by the high quality of the sessions offered as well as the expertise and reputation of the speakers. Participants came from a variety of disciplines including but not limited to IPs, infectious disease physicians and researchers, public health professionals, academics, and frontline healthcare workers. Speakers included renown researchers and experts from (among others) academia, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), and the World Health Organization (WHO). In case you are wondering, the conference was entirely in English with the provision of simultaneous translation equipment available at every seat.

The excitement at the ICPIC opening ceremonies was palpable and set the tone for the rest of the conference. In her opening remarks, Celine Gardio, Program Director for the Swiss Federal Office for Public Health, provided a call to action to get IPC back on track following the pandemic. Tedros Ghebreyesus, WHO General Director, reminded participants that “without correct IPC, hospitals can become transmitters of infection.” He stated that “hospitals should be places of health, not harm,” yet a sobering statistic remains that globally, most HAIs are AMR. This was a great introduction to the WHO’s new global strategy on IPC, an operational framework using change theory on those actions needed to reduce HAIs, AMR, and infectious disease outbreaks by the year 2030. Dr. Michael Bell, Deputy Director of the U.S. CDCs Division of Healthcare Quality Promotion echoed the concerns of his international colleagues with the growing threats of AMR. I encourage IPs to review the following tools provided by the WHO.

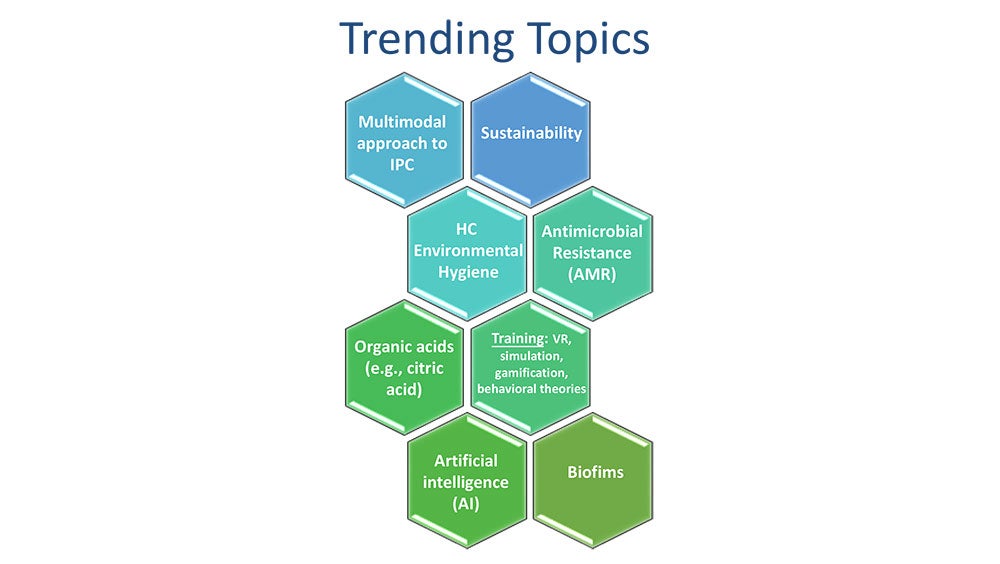

Over the course of the next two-and-a-half days, I attended a plethora of excellent general sessions, keynotes, and symposiums. The over-arching theme of the conference encompassed moving forward in a post-pandemic world. See Image 1 for topics that trended throughout the week.

One trending topic that seemed to be woven throughout the conference sessions, even more so than hand hygiene, was healthcare environmental hygiene. This important topic was finally given the attention it deserves and was emphasized in multiple sessions by the US and international experts alike. Selected experts, including Dr. Didier Pittet (Switzerland), Dr. Alexandra Peters (Switzerland), Dr. Pierre Parneix (France), Dr. David Calfee (US), and Jon Otter, PhD (UK) from the global Clean Hospitals Initiative led a very well-attended symposium dedicated to this topic. The Clean Hospitals Initiative is a network of experts and industry partners (including Clorox Healthcare) working together to make hospitals safer through improved environmental hygiene through academic research, education and training, and raising awareness (learn more here from my recent interview with Dr. Didier Pittet). I truly appreciate how the experts tied a clean environment to clean hands. You can’t have one without the other. I am sure you have all heard me say over the years that our hands are only as clean as the environmental surfaces around us. In a session titled “Are we prepared for future challenges in IPC”, Vanessa Vazquez, a healthcare IP leader (Spain), reminded participants that “infection transmission is not only about our hands”, while another expert panelist, Dr. Moi Lin Ling, Director of Infection Control, Singapore General Hospital, added that “we must pay more attention to environmental hygiene - much like we also do for hand hygiene.” We know that environmental contamination leads to HAIs and that admission to a room previously occupied by a patient with an AMR pathogen, including C. difficile, significantly increases the risk for the next patient admitted to the room to acquiring that pathogen.1,2 In fact, Dr. Alexandra Peters with the Clean Hospitals Initiative and the Hospital University of Geneva (HUG) reported that over the last 20 years, we are seeing a shift towards outbreaks of gram-negative pathogens which are often found in the healthcare environment. Dr. David Weber (United States), in his session on “no-touch room disinfection,”, shared that 20-40% of HAIs are associated with either environmental contamination or cross-contamination. But the good news is that “improving cleaning strategies improves patient outcomes” (Dr. Parneix).

"Our hands are only as clean as the environmental surfaces around us."

– Doe Kley, Infection Prevention Fellow, Clorox Healthcare

To help IPs and environmental services professionals improve their environmental hygiene programs, Clean Hospitals recently released their comprehensive and validated Healthcare Environmental Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework (HEHSAF) – a new tool with the dual purpose of assessing the level of need, but also for improving a facility’s performance by utilizing it as a benchmark for improvement over time. The HEHSAF is based on the Multimodal Improvement Strategy and focuses on both the technical and human elements of healthcare environmental hygiene. This tool, developed by Dr. Pittet and team, follows in the success of a similar tool (“Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework”) developed back in 2010 by this team in collaboration with the WHO. Many IPs reading this blog may be familiar with this tool — I know I employed to improved hand hygiene at my last hospital. I encourage IPs and EVS to work together to complete the HEHSAF which is currently available in 7 languages with more coming.

"Clean care is safer care, a basic patient right"

– Aleksandra Maczynska (Ireland)

To end on a less serious note, I would like to share what I learned in a really awesome session titled “Space: The Final Frontier” presented by Dr. Leonard Mermel, a researcher at Brown University (United States). We know that IPs work in a variety of settings, but did you know that even the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) employs IPs? If you ever find yourself on Mars, here is what you need to know about life (and health) in a zero-gravity setting:

- Humans become immunosuppressed in space.

- In contrast, microbes grow exuberantly, have enhanced virulence, increased drug-resistance, and a lower infectious dose.

- Chronic viruses (e.g., Epstein Barr Virus, Cytomegalovirus, Varicella) are reactivated.

- When an astronaut coughs or sneezes or flushes the toilet, the droplets remain suspended in the air indefinitely posing unique IPC challenges.

In closing, I give the ICPIC conference a 10 of 10. In response to my own question regarding IPC challenges posed at the opening of this blog, it should not have come as a surprise to learn that IPs across the globe struggle with the same challenges that you and I face every day. Whether you practice in a low-resourced country versus a higher resourced country, perhaps you’ll find it reassuring to know that we all face the same issues in getting staff to consistently comply with IPC practices, including hand hygiene. Pathogens don’t respect state or country borders, but when we work together towards the same goal, we can (and do) make a difference. Because the ICPIC conference was so rich in information, please be on the lookout for a second blog sometime in the near future covering some other great content. I will close with one of my favorite quotes of the week regarding the comparison of healthcare errors to the aviation industry:

"If a pilot crashes, he crashes with his passengers. If a clinician 'crashes,' only the patient is harmed."

– Dr. Andreas Widmer, Swissnoso (Switzerland)

We can and we must improve.

References

1. Weber D, Kanamori H, Rutala W. ‘No touch’ technologies for environmental decontamination: focus on ultraviolet devices and hydrogen peroxide systems. Curr Op Infect Dis. 2016;29 (4).

2. Weber D, Anderson D, Rutala W. The role of the surface environment in HAIs. Curr Opinion in Infect Dis. 2013.

Doe Kley, Infection Prevention Fellow within Clorox Healthcare’s Clinical and Scientific Affairs Team, recently sat down with Professor Didier Pittet of the University of Geneva, Switzerland and Chair of Clean Hospitals to discuss new research, Clean Hospital’s mission and how healthcare professionals can limit the spread of healthcare-associated infections.

With these topics top of mind worldwide, play the video above or keep reading to hear their thoughts.

Please note this is an abridged version of the interview edited for brevity and clarity.

What Is Clean Hospitals?

Doe Kley: Hello, everyone. My name is Doe Kley. I'm an infection prevention fellow with Clorox Healthcare's Clinical and Scientific Affairs Team. I'm a little bit starstruck today because I'm joined by Dr. Didier Pittet to discuss his current work with Clean Hospitals, all the way from Geneva, Switzerland. Welcome, Dr. Pittet. Would you like to introduce yourself and the Clean Hospitals Initiative?

Professor Didier Pittet: Thank you, Doe. It’s a pleasure to be with you today. I'm Professor Didier Pittet from the University of Geneva in Switzerland, and we started the Clean Hospitals initiatives several years ago as a way to partner together to improve patient safety and reduce healthcare associated infections and patient harm in hospitals.

Leveraging the Clean Hands Initiative Framework

Doe Kley: That is awesome. I know that you led the team with the World Health Organization that revamped the hand hygiene guidance. I'm really excited to see what Clean Hospitals accomplishes. I'm curious, was there something that you learned from your hand hygiene work that led you to this next initiative?

Professor Didier Pittet: Absolutely. In fact, the Clean Hospitals Initiative is built on the model that we use for the so-called Clean Hands initiatives or the Clean Hands Save Lives.

First, we did a review of the literature. Is healthcare environmental hygiene important? The answer is yes. You could look at our systematic review that we published a few years ago, that revisited all the studies in the literature, and we paid attention in this review to exclude studies where hand hygiene was promoted. Why? Because we know that if you succeed at promoting hand hygiene, then it would be difficult to monitor the impact of improving healthcare environmental hygiene in reducing infections.

But this systematic review was the first deep research of the Clean Hospital Initiative. [It] was there to help raise awareness about the importance of the role of healthcare environmental hygiene. Then we developed instruments that we already developed for hand hygiene. You probably know the hand hygiene self-assessment framework that we developed in 2009, and we launch globally all over the world.

We have been developing the healthcare environmental hygiene self-assessment framework that we will be launching at the next Clean Hospitals Day worldwide on the 20th of October this year. These are instruments that we used for hand hygiene promotion that we are using in the model of the Clean Hospitals Initiative.

Doe Kley: That's awesome. I'm super excited to get my hands on that self-assessment and share it with some of our customers. I am very familiar with the hand hygiene assessment [and I] used it at my last hospital. It's really incredible to hear about this impactful and inspiring work. Thank you for tackling this important patient safety topic.

The Recipe for Environmental Hygiene

Doe Kley: Beyond what you just shared, I also know that Clean Hospitals champions high-quality products, processes for environmental hygiene. Can you talk just a little bit about this? For example, what does your research show as it relates to the importance of environmental hygiene and patient outcomes or HAIs?

Professor Didier Pittet: If you succeed at implementing a healthcare environmental model program that improves the practices by using not only the right product but the right procedures and sometimes the right people — or training the right people to use the right procedures — you could demonstrate a very significant impact on healthcare associated infections, but also on the transmission of multi resistance, multi resistance and bacteria or multi resistant organism.

This was very revealing of the importance of a multimodal approach for improving healthcare environmental hygiene, something that we know very well in infection control. That's what Clean Hospitals is working on in order to spread this strategy all over the world, using the best partners from all around the world.

Doe Kley: Thank you for that. And I can very much resonate with the multi-modal strategy, especially when you touched on antimicrobial resistant pathogens. We put so much focus and emphasis on antimicrobial stewardship, [it’s] very, very important, but I think we overlook that a clean environment is equally as important. I also think that we are not entering — I think we are in the post antimicrobial era. So even more important now, more than ever before. Thank you for this work and thank you for touching on that.

Ready-to-Use Disinfectants

Doe Kley: Do you have thoughts on ready to use disinfectants in terms of patient safety and [the disinfecting] process?

Professor Didier Pittet: Yeah, of course. The [Clean Hospitals] strategy is a worldwide strategy. So of course, the recommendations may vary from one region of the world to another. Not that bacteria are changing, but that resources are not the same. Sometimes we have only resources that are very simple, but at least we need to make sure that the procedures, the process of cleaning is at the top.

Staff Training

Professor Didier Pittet: That's why we are always adapting the strategy to the level of care and to the resources that are available. Today, we have many approaches to clean the environment. The most important is how are you doing it: with what product, with what technique, and who is doing it. Making sure that people who are performing those processes understand those processes very well. But we need to adapt the technique. The education should be adapted to anybody applying the technique. For us at Clean Hospitals, this is extremely important.

Clean Hospitals Self-Scoring System

Doe Kley: I could not agree more. You know, at Clorox Healthcare, we are huge advocates for compliance, effective [and] efficient cleaning and disinfection. We know it starts with education, training and competency. I think competency is the piece that often gets overlooked. Do you have any thoughts on approach towards achieving competency in our in our cleaning staff?

Professor Didier Pittet: Yes. We have developed a scoring system that will be launched at ICPIC, the Congress in Geneva, but then launched worldwide on Clean Hospitals Day. When you look at the scoring system, it is appreciating. It’s a self-scoring system where you can appreciate the level of your institution. How ready is your hospital? Is your healthcare institution able to have [the] environmental hygiene program adapted to your institution?

In the scoring system, we are looking at the product, we are looking at the process, we are looking at the education. Of course, all of these help us to actually redirect or help the way people can teach, the way people are learning, the way people are implementing. As you know today, infection prevention and control implementation is extremely important.

I know at Clorox you are making sure the implementation of the good product and the good process is a reality and that's extremely important for this. You can use all sorts of techniques, but the most important is to make sure that you are working on the way to implement the best strategies and the best product.

What to Expect at ICPIC

Doe Kley: Perfect. I'm sure that these topics are going to be a focus at this year's International Consortium for Prevention and Infection Control, or the ICPIC conference that you mentioned. Can you share a little bit about Clean Hospitals presence at ICPIC.

Professor Didier Pittet: Clean Hospitals partners [Clorox] will be at the Clean Hospitals booth, where we will show our activities [and] promote our next activities. We will speak about the activities around upcoming Clean Hospitals days.

We will share about our knowledge in the field of healthcare environmental hygiene. There will also be a Clean Hospitals symposium, because at ICPIC we want people to understand the Clean Hospital initiatives and we ask our best international experts from around the world to come and deliver a lecture. We will also have four poster sessions in the field of healthcare and hygiene.

We will have more than 200 posters just in these fields of hand hygiene, healthcare environmental hygiene, from more than 60 countries around the world. Last but not least, Clean Hospitals partners will be there to share and share and share, which is so important for us today in our field.

Doe Kley: I couldn't agree more. It is so exciting to see the increase in activity in the science and the protocols that go into environmental planning and disinfection. I think Clean Hospitals has already started to make a great impact there. Thank you for helping to elevate the hard work. Do you have any final thoughts that you'd like to share with us all Dr. Pettit?

Professor Didier Pittet: We have been saving lives all over the world with the Clean Hands initiative — between 5 and 8 million lives every year around the world — but we know that we can save even more lives. [It’s] so good to have partners like Clorox, among the best partners around the world, being with us in this Clean Hospitals initiative; it's a pleasure and a privilege.

Doe Kley: Thank you. That privilege is all ours. Thank you for inviting us in.

While it may have been 107°F in Dallas, the hottest topic at the 2023 Exchange Conference was emerging and high-consequence pathogens. The conference hosted each year by the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE), allows for the exchange of evidence-based best practices and solutions. With emerging pathogens continuing to be a top concern for healthcare facilities, staying up to date is critical for Environmental Services (EVS) leaders and Infection Preventionists (IPs) to effectively eliminate the environment as a source of infection. I was fortunate to have the opportunity to present on the implications of cleaning and disinfecting against emerging pathogens in a session titled “Know the Enemy: Deepening Your Understanding of Environmentally Spread Emerging Pathogens.” In this post, I will share some of the key takeaways from this practical session.

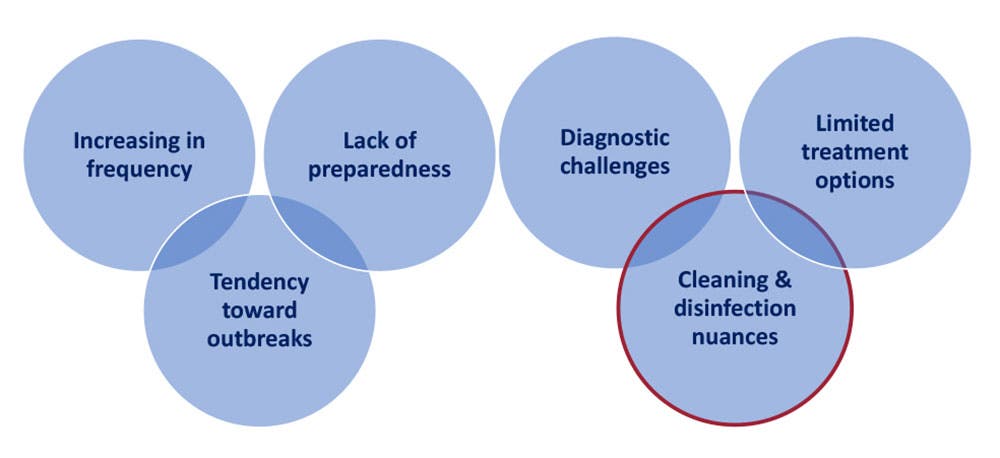

6 Challenges with Emerging Pathogens

Emerging pathogens come with their own set of unique challenges. Global changes in recent decades have resulted in increased spill-over from animal to human hosts, often catching us under-prepared. Because of the diagnostic and treatment challenges inherent with a novel pathogen, transmission can go unchecked resulting in outbreaks. Finally, there can be implications for cleaning and disinfecting against a novel pathogen.

Cleaning & Disinfection Implications

Some general considerations as they relate to cleaning and disinfecting against emerging pathogens include:

- Product: For emerging pathogens, it’s imperative to select appropriate disinfecting products. However, because the pathogen is novel, it is not likely that any disinfectant on the market will have claims against it — at least not right away. Adding new claims to an existing product does not happen overnight. It takes about a year to get these claims approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Additionally, some disinfecting chemistries may be more effective than others against a given pathogen. For example, disinfectants with quaternary ammonium compounds (e.g., “quats”) as the only active ingredient have not been found to be effective against Candida auris.1

- Training: Staff will need to be educated, trained, and competent to safely and effectively clean and disinfect against a new pathogen. Consider having a dedicated cleaning team to respond to these pathogens. In addition to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidance, the National Emerging Special Pathogens Training and Education Center (NETEC) is another great resource.

- Process: There is the need to identify a process for managing the pathogen. For example, protocols should include the personal protective equipment (PPE) to be worn to enter the room, the appropriate disinfectant to be used, and the cleaning frequency. Again, see CDC and/or NETEC guidelines and resources.

- EPA: As the regulatory body over disinfectants, it is essential to be aware of any specific policies, requirements, or resources as they relate to novel pathogens. Some examples include the EPAs Emerging Viral Pathogen Policy and the EPA Disinfectant Lists that should be leveraged to find appropriate products.

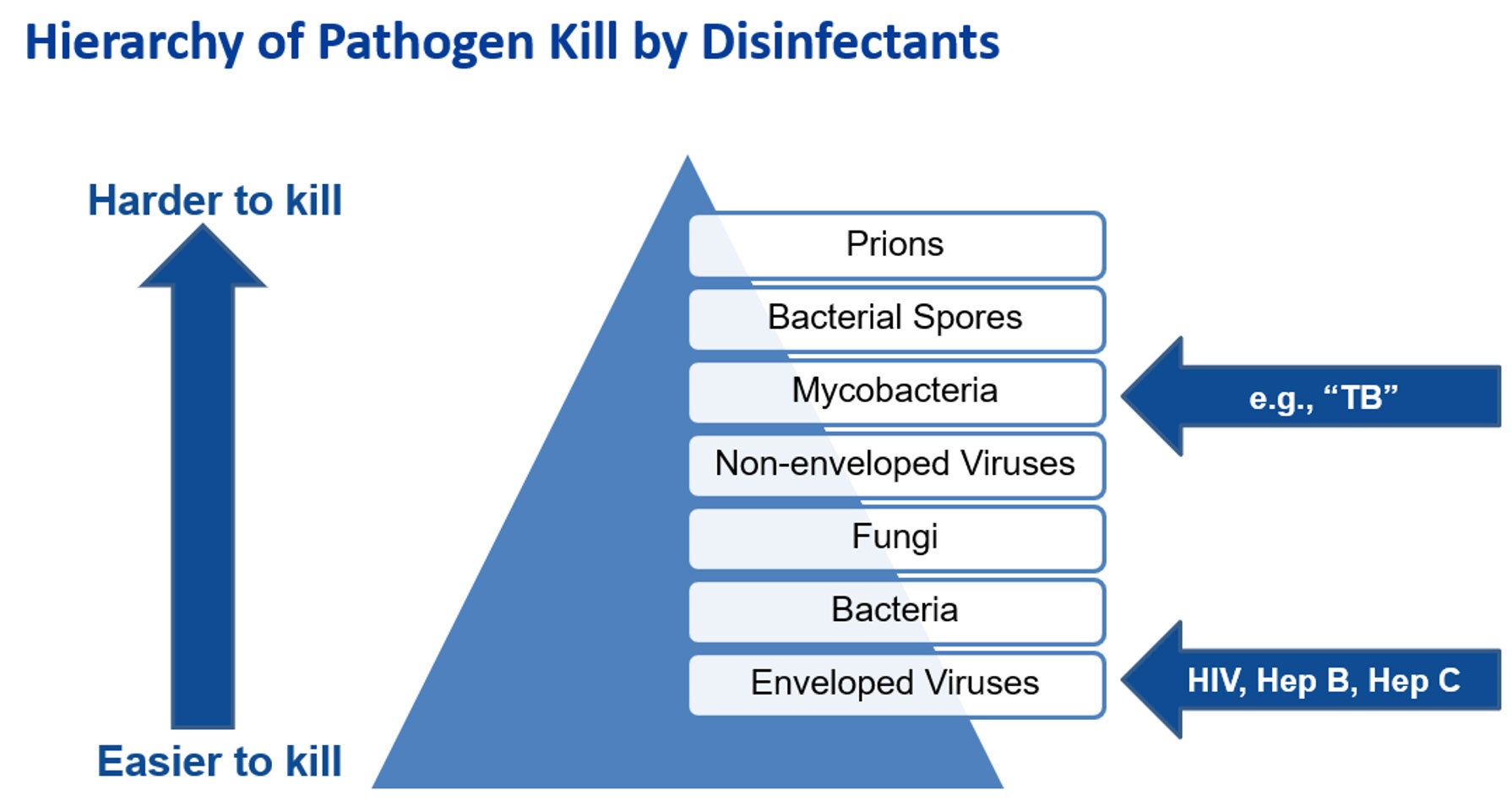

Leveraging the Hierarchy of Pathogen Kill by Disinfectants

As guidance from the CDC and EPA may not be immediately forthcoming in the early weeks of the emergence of a new pathogen, it is imperative to have a plan. In the interim before the EPAs Emerging Viral Pathogen policy is activated, I recommend using a sporicidal, like bleach, because it is broad-spectrum against hard-to-kill pathogens. I also recommend creating job action sheets specific to the emerging pathogens of concern. These should describe the roles and responsibilities for each discipline. For example, an EVS Job Action Sheet for Candida auris could include the precautions to be taken and which disinfecting product to use (e.g., EPA List P).

Understanding the EPAs Emerging Viral Pathogen Policy and List Q

It is important to note that the EPA’s Emerging Viral Pathogen policy only applies to viruses. It does not apply to emerging bacteria, fungi, or other pathogens. This policy is activated once the CDC declares an outbreak of the emerging virus. This means that products meeting EPA’s List Q criteria can be used - unless there is a more targeted list – for example, EPA’s List L for Ebola. Many disinfectant manufacturers already have the EPAs Emerging Viral Pathogen claim on some or all of their products, so it is ready to go in the event of a novel virus.2,3

List Q is unique from the other EPA Lists because it does not target a specific pathogen. With this List, the user searches for eligible products for use against an emerging pathogen by selecting the appropriate tier based on virus type. To navigate List Q, the user will need to know whether the emerging pathogen is:

- An enveloped virus (tier 1- the easiest of the 3 types to kill),

- A large non-enveloped virus (tier 2), or a

- A small non-enveloped virus (tier 3 - the hardest of the virus types to kill).

Lastly, it is important to understand that because a given product from List Q meets the criteria for use against one emerging virus (e.g., Mpox), it does not mean this product will be effective against any future emerging viruses. It is designed to be used on a pathogen-by-pathogen basis.4

The 21st century world is being impacted by emerging infectious diseases on an unprecedented scale.5 Preparedness is key to control and containment. Attendance at conferences such as AHE Exchange is one way for EVS leaders and IPs to stay one step ahead of the next new pathogen. We need to be better prepared than we were for COVID-19. Robust and adaptable protocols for cleaning and disinfection are a great place to start.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Prevention and Control for Candida auris [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-infection-control.html

2. US Environmental Protection Agency. What is an Emerging Viral Pathogen Claim [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/coronavirus/what-emerging-viral-pathogen-claim

3. US Environmental Protection Agency. Guidance to Registrants: Process for Making Claims Against Emerging Viral Pathogens Not On EPA-Registered Disinfectant Labels [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/emerging-viral-pathogen-guidance-and-status-antimicrobial-pesticides

4. US Environmental Protection Agency. Disinfectants for Emerging Viral Pathogens (EVPs): List Q [Internet]. [cited 2023 Aug 14]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/disinfectants-emerging-viral-pathogens-evps-list-q

5. Ambat A, Vyas N. Assessment and preparedness against emerging infectious disease among private hospitals in a district of South India. Open Access: Med J Armed Forces India [internet]. 2022;78(1):42-46.

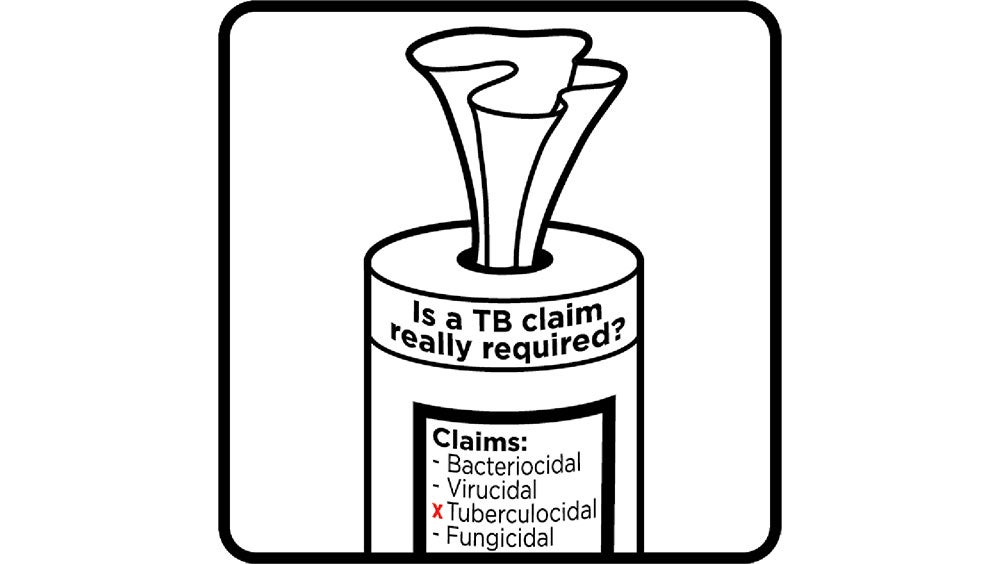

Is it true that healthcare disinfectants must have a tuberculocidal (TB) claim? It’s an age-old belief held by many infection preventionists (IP) that healthcare disinfectants must have a TB claim. We did some digging and have published our findings in our latest white paper.

I recall a time when the manufacturer of the disinfectant we used at my hospital had removed the TB claim from the product. The corporate IP informed us that we must find a replacement product that had a TB claim. When I queried as to why, I was told it was a requirement. Knowing how disruptive it can be to switch products and being a very inquisitive and evidence-based IP, I started on a quest to find this “regulation”. I looked at both the local and federal government level and after an exhaustive search, I found no such requirement. After starting in my new role at CloroxPro, I shared this experience with my colleagues which started us on down a discovery path to identify this source of this misinformation. A white paper on this topic is the culmination of our research.

The purpose of a TB claim on surface disinfectants is not for the prevention or control of transmission of tuberculosis, an airborne-spread disease, which is not transmitted via contaminated surfaces or fomites. Rather its purpose is to serve as a benchmark of disinfectant antimicrobial efficacy. This is because Mycobacteria (the genus which TB belongs to) are notoriously difficult to kill with disinfectants. Disinfectants that have a TB claim are considered intermediate-level disinfectants. Yet, according to the Spaulding scheme, no greater than low-level disinfection is necessary for environmental surfaces and non-critical medical equipment (e.g., equipment that only contacts intact skin).

"The purpose of a TB claim on surface disinfectants is not for the prevention or control of transmission of tuberculosis."

Why is it important to understand that a TB claim is not a requirement? Because two of the leading properties of an ideal disinfectant are a short contact time and good surface compatibility. Harder to kill pathogens, like Mycobacteria (e.g., TB) require tougher disinfectants, which often have longer contact times and less-than-desirable compatibility with surfaces and equipment. Achieving a TB claim also increases the cost of the product. Insisting on a TB claim limits your disinfectant options. Many manufacturers opt not to pursue this unnecessary claim given these downsides as well as the fact that harder-to-kill pathogens like C. difficile are now available for testing.

"Insisting on a TB claim limits your disinfectant options."

But where did this misbelief of requiring a TB claim come from? We learned that it came into being in the early years (and fears) of the HIV epidemic, before the causative agent had been identified, and before we knew how easy (or hard) it was to kill with disinfectants. However, the Cleaning Industry has come a long way over the past 40 years. Many, if not most, of today’s EPA-registered healthcare-grade disinfectants have kill claims for the bloodborne pathogens of most concern (e.g., HIV and Hepatitis B and C viruses) negating the need for the TB claim. In fact, these enveloped viruses are among the easiest pathogens to kill. As a result, OSHA revised their definition of an appropriate disinfectant for blood and body fluid clean up to include those with HIV and Hepatitis B kill claims.

"Many, if not most, of today's EPA-registered healthcare-grade disinfectants have kill claims for the bloodborne pathogens of concern."

Figure 1.

It’s time for this now debunked belief that a TB claim is required to be put out to pasture once and for all. Learn more from our white paper titled “Clearing up the confusion: why a tuberculocidal claim on surface disinfectant is no longer needed."

Environmental service (EVS) professionals play a crucial role in infection prevention and control by eliminating the environment as a source of infection. Continuing education helps EVS leaders bring their “A-game” and help their teams perform at the highest level possible. Because of this, Clorox Healthcare® is happy to introduce a new best-in-class microlearning module that is part of our CloroxPro HealthyClean® online learning platform. EVS professionals will benefit from this interactive course created to deepen understanding of healthcare-specific cleaning and disinfection. We collaborated with instructional designers to ensure that the needs of adult learners are met. No products are promoted in this short training — it includes only the essentials on what busy EVS professional need to know.

Because healthcare operations are incredibly complex, continuing education is a given for professionals working in healthcare. Healthcare EVS have a very serious mission: keeping patients, visitors, and healthcare workers free from exposure to infection-causing pathogens. Healthcare EVS must understand how pathogens are transmitted within their facilities — including from contaminated environmental surfaces. Cleaning healthcare spaces, like operating rooms and isolation rooms, requires a very specialized skill set that can only be achieved through ongoing education and training. Time spent on education and training is never in vain. The benefits include improved skills and possible career advancement. When an employee adds skills to their “toolbox”, their value to their employer is increased. Additionally, relevant certificates demonstrate to future employers skills that the competition may not have.

What will participants learn in this new training titled “An Introduction to Cleaning and Disinfection in a Healthcare Setting”? Available in both English and Spanish, this course addresses both the need and the nuances of cleaning and disinfecting in this specialized setting and includes some of the different types of cleaning (e.g., occupied, terminal, isolation, etc.). Additionally, participants are pointed to several great resources and there are even a few case studies to help the learner to apply the lessons learned. More specifically, participants will learn:

- What infection prevention and control (IPC) is

- The role that EVS play in IPC in a healthcare setting

- What a healthcare-associated infection (HAI) is

- The standard precautions and transmission-based precautions used to prevent HAIs

- Best practiced when cleaning and disinfecting patient areas

This module meets many of the same quality training standards that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has established for their trainers and educators.1 This includes content that is accurate and relevant and that provides opportunities for learner engagement. Upon completion of this training and passing a short quiz, the participant will receive a certificate of completion. Course completion can be added to one’s resume and the certificate can proudly be displayed in an office or even on LinkedIn for all to see. And if interested, we also offer a HealthyClean Trained Specialist course for frontline EVS that is accredited by the ANSI National Accreditation Board (ANAB).

For a limited time, you can access the New Healthcare Microlearning Module at no cost by registering here and entering promo code 0323 at checkout. If you have any question or need any help registering, contact the CloroxPro HealthyClean Certificate Program Team at cloroxpro.healthyclean@clorox.com.

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Training Development: Quality Training Standards [Internet]. [Cited 2023 Feb 13]. Available from CDC.

It has been over 3 long years since the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE) Annual Exchange Conference was held in-person. AHE is the professional organization for healthcare environmental services (EVS) professionals and the Annual Exchange Conference gathers these EVS leaders for knowledge sharing, exchange of best practices and ideas, and connecting with peers. Despite an ongoing pandemic and a category 3 storm (Hurricane Ian), nothing was going to stop over 400 of us from attending this year’s event in Orlando, Florida! I can’t express the joy in seeing the smiling faces of old friends and colleagues again. Together we partook in fun social events, ate good food, strolled a right-sized exhibitor hall, and networked. And not to forget, there were some great educational sessions including topics as such as:

- Pathogens of interest (e.g., Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) and Candida auris)

- Emergency preparedness

- Future of EVS

- Continuous survey readiness

- Cleaning and disinfection (of course!)

A common theme heard from an overwhelming majority of attendees was the staffing challenges as a result of the Great Resignation. Keynote speaker DeDe Halfhill, a leadership expert, shared that we are seeing burnout at levels we have never seen before. She advised EVS leaders to be vulnerable and lead with love through staff engagement. Leaders should communicate to connect at a human level, not simply to direct. Keynote speaker, Kim Seeling Smith, a future-of-work and talent retention expert, informed attendees that 80% of workers would choose a caring boss over a 20% pay increase. People must be in the center, and we can do this through respect, trust, collaboration, communication and inclusiveness.

Ms. Seeling further reported on some the causes of the worker shortage including self-employment, competition, and retirement. Baby Boomers are retiring at a rate that exceeds the younger generations entrance into the workforce and this is not expected to correct until 2030. Today’s workforce has become more empowered and to retain them, we need to help them to achieve their goals - all while still getting the work done. People come to work to add value. As leaders, it’s our job to help them understand that what they do is meaningful – they help to keep patients healthy and alive through the provision of a sanitary environment cleaned to acceptable healthcare standards. I really appreciated this hiring tip provided by Ms. Seeling:

“Don’t hire for experience, rather jot down the 5 strengths needed for the job and hire accordingly. You can always train them on the necessary skills.”

— Kim Seeling Smith

Several attendees shared the creative ways in which they are recruiting workers. One facility reported hiring high school students part-time, while another facility developed a re-entry program for veterans and recently released incarcerated persons.

Once you have the right people in place, you need to get them up-to-speed quickly through education and training. A well-trained staff is an efficient machine so checkout some of our short Clorox Healthcare training videos:

- Occupied Patient Room Cleaning

- Discharge/Terminal Patient Room Cleaning

- Operating Room Between Case Cleaning

- Operating Room Terminal Cleaning

As a leader, it is important to stay current with your own education so I recommend checking out our new CloroxPro™ HealthyClean™ online learning platform for best-in-class education and training. HealthyClean™ offers the only industry-wide certificate course designed for the commercial cleaning industry to be accredited by the American National Standards Institute National Accreditation Board (ANAB).

Other time-saving tips include the use of ready-to-use one-step cleaner-disinfectants. These products save your staff time while eliminating the risk of dilution errors. Additionally, there are no secondary bottles to label and to have to clean, disinfectant, and dry after each use as recommended by the CDC.

Thanks for reading and I hope to see you all in Dallas at the 2023 AHE Annual Exchange Conference! In the meantime, be on the lookout for our new healthcare-specific HealthyClean™ training coming soon!

Introduction

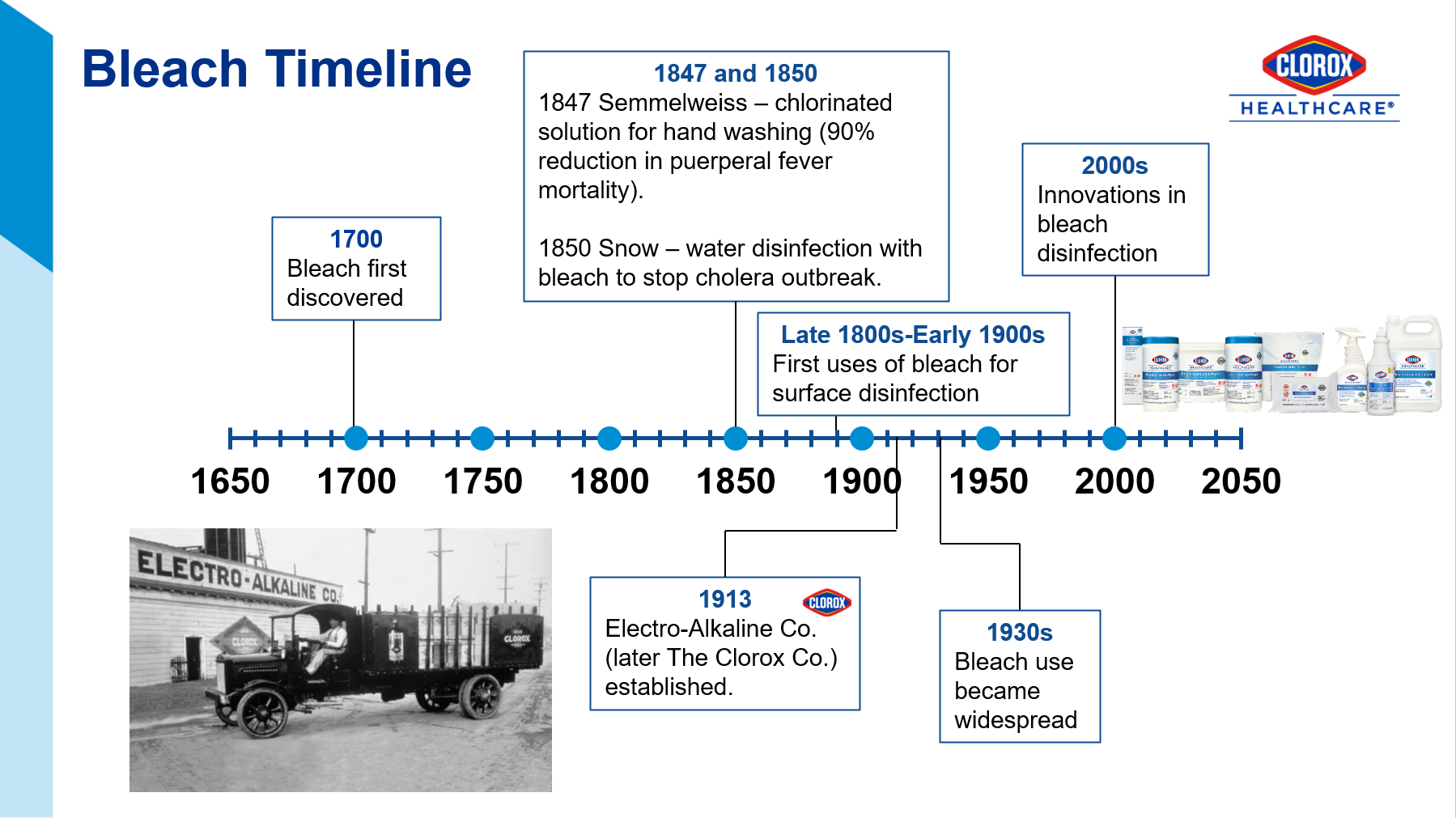

Healthcare facilities have many options when it comes to surface disinfectant selection. While no one product checks off all of the boxes of the ideal disinfectant (Figure 1), I will share why I think bleach is B.E.S.T. in this article. I will start with a brief history of bleach, tackling tough pathogens, responsible bleach use, and the critical moments for bleach use.

The Joint Commission recommends that healthcare facilities limit the number of disinfectants to 2-3 products with at least one having a sporicidal claim, like bleach.1 Sodium hypochlorite (the active ingredient in bleach), has withstood the test of time since its discovery in the late 1700s (Figure 2)2. This is because it is relatively inexpensive, readily available, and has efficacy against a broad range of pathogens.

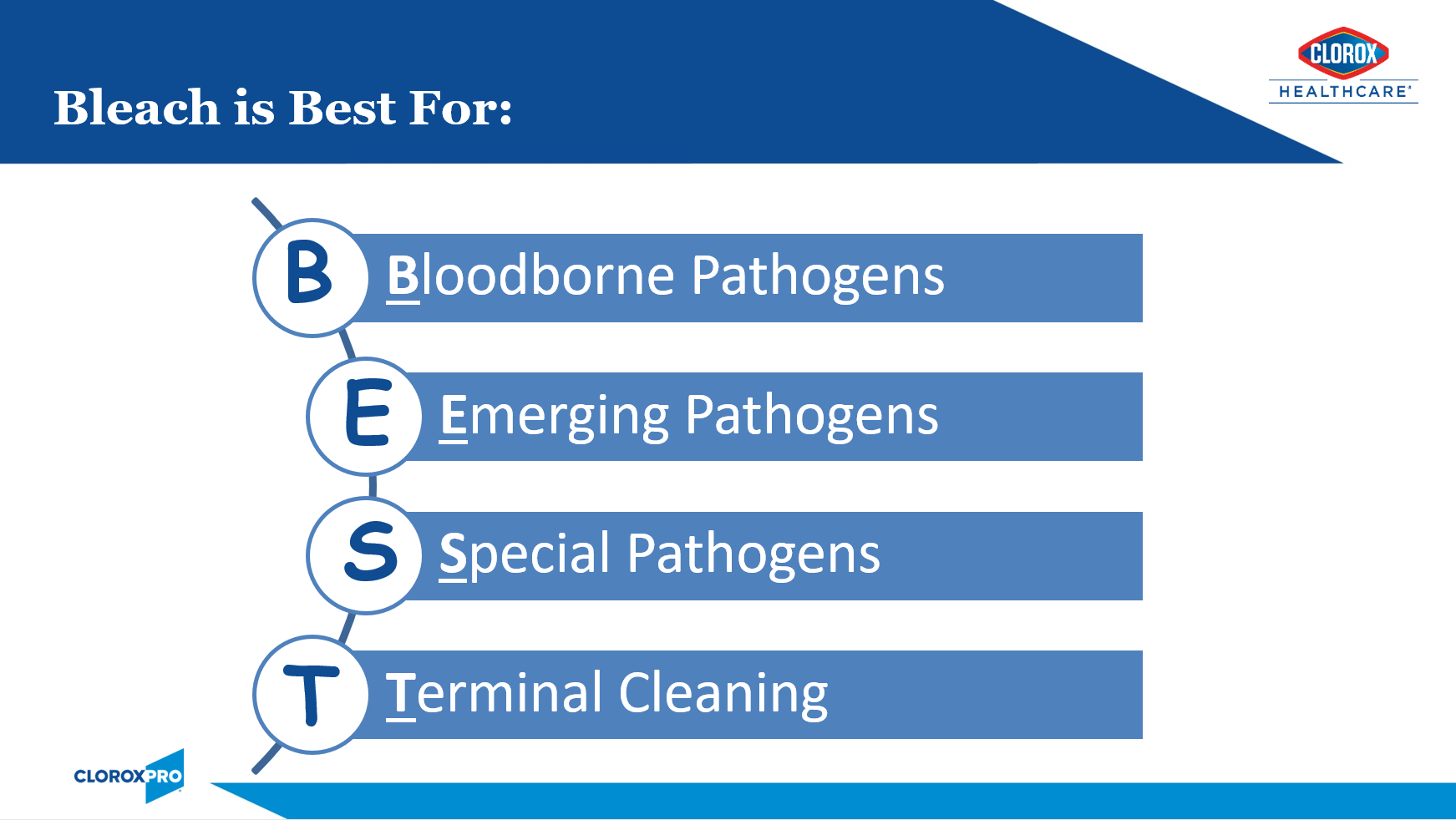

B.E.S.T. Use Indications for Bleach

Innovative chemists have developed lower-level sodium hypochlorite products that offer good surface compatibility, low odor, and acceptable contact times while still being sporicidal. Our compatibility program has endorsements from key equipment manufacturers. See Appendix A for a range of bleach products to address different needs. While these improved bleach formulations are gentle enough for everyday use, shared here are some of the most critical moments for its use. The mnemonic B.E.S.T. will help you to remember these key moments (Figure 3).

- Bloodborne Pathogens:

- For cleaning and disinfection of blood or body fluid spills, the CDC recommends a 1:100 (small spills) or 1:10 dilution (large spills) of 5% bleach.3 The EPA Master Label for pre-diluted ready-to-use bleach-based disinfectants should provide information on the products dilution ratio.

- Emerging and Re-emerging Pathogens:

- Bleach is often the go-to disinfectant active for emerging or re-emerging pathogens. Examples include:

- COVID-19: While products with the EPA-approved emerging viral pathogen claim (List N) are expected to kill SARS-CoV-2, there were supply chain issues during the pandemic. Bleach to the rescue! Many facilities relied on “jug” bleach diluted in accordance with CDC recommendations.4

- Novel Influenza strains: I specifically recall the H1N1 pandemic of 2009. Since this was before the EPA had implemented their Emerging Viral Pathogens policy, the CDC had recommended use of bleach until more was learned about killing this viral strain.

- Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii (CRAB): According to CDC special report earlier this year, the incidence of CRAB increased 78% during the pandemic.5 This problematic emerging pathogen is difficult to eradicate due to its ability to survive for prolonged periods in the environment. The CDC recommends enhanced cleaning and disinfection. A recent of outbreak of CRAB in a South Korea hospital was eventually contained when twice daily disinfection with bleach was implemented.6

- Ebola: While historical Ebola outbreaks have mostly been contained to the African continent, the current outbreak in Uganda, again raises concerns for imported cases. Emergency preparedness means having appropriate products on-hand. The CDC recommends the use of an EPA-registered hospital disinfectant from List L.7 I am particularly proud of the fact that the Clorox Company is the only disinfectant manufacturer with EPA-registered label claims against the Ebola virus.

- The above examples are all viral. Please note that the EPA Emerging Viral Pathogens Policy only applies to viruses. It will not apply should the next emerging pathogen be a bacterial or fungal in nature. For this reason, it’s a great idea to ensure that you always have bleach on-hand.

- For additional reassurance against these troublesome pathogens, consider use of adjunct disinfection such as electrostatic technology to ensure that all surfaces and nooks and crannies are covered. You will need to ensure that the product is EPA-approved for use through electrostatic sprayers.

- Bleach is often the go-to disinfectant active for emerging or re-emerging pathogens. Examples include:

- Special Pathogens — Two of the most troublesome pathogens that call for enhanced infection control measures to control their spread, are outlined here:

- Clostridiodes difficile (C. diff):

- C. diff remains one of the most common causes of healthcare-associated infections.8 The hardy spores can persist in the environment for many months and are very difficult to kill (see Figure 3 above). These spores can be picked up on the hands of healthcare workers and transmitted to other patients. Until recently, bleach was the only sporicidal disinfectant available to kill C. diff spores. With the use of bleach and other infection prevention efforts, the HO-CDI standardized infection ratio (SIR) has decreased from 0.85 in 2016 to 0.48 in 2021.8,9 There is an abundance of studies demonstrating the effectiveness of bleach in reducing HO-CDI rates (Appendix B). While we have made recent strides in reducing HO-CDI rates (hooray bleach!), we must remain vigilant as community-acquired C. diff incidence is on the rise.10 As these patients seek medical attention, the pathogen can get re-introduced into our facilities. Click here for a great C. diff Terminal Cleaning Protocol & Checklist.

- Candida auris (C. auris):

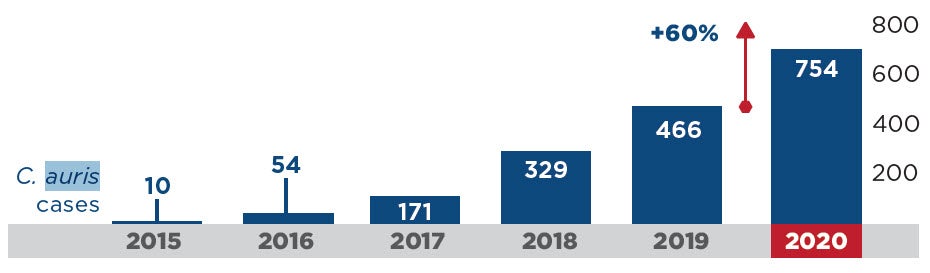

- This emerging threat is a very worrisome multidrug-resistant yeast with a mortality rate between 30-60%. During the pandemic, HAIs caused by C. auris increased an alarming 60% (Figure 4).5 Because this pathogen is transmitted by the contact (or touch) route and because it persists in the environment for prolonged periods, it spreads rapidly in healthcare settings. It can be very difficult to eradicate and outbreaks often result. Several outbreaks documented in the literature reported enhanced cleaning and disinfection with bleach successfully contained the outbreak.11,12 In fact, the CDC recommends using an EPA-registered hospital-grade disinfectant effective against C. auris or C. diff spores, including bleach.13 Click here to learn more from my C. auris webinar (free CE’s!).

- Clostridiodes difficile (C. diff):

COVID-19 Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance in the U.S.

- Terminal Cleaning:

- Several studies have shown that patients admitted to rooms previously occupied by individuals infected or colonized with MDROs or C. diff are at up to three times higher risk of acquiring these pathogens.14 CMS requires that after a patient vacates a room, all visibly or potentially contaminated surfaces are thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.15 Each patient deserve the highest level of surface cleaning and disinfection, therefore I recommend, at a minimum, using a bleach-based cleaner-disinfectant for all discharge and isolation cleanings.

Responsible Bleach Use

After nearly 3 years of dealing with pandemic, including staffing and supply chain issues, practices may have drifted from our written protocols. For example, are staff being compliant with bleach use when it’s indicated? It’s now time that we reassess our cleaning and disinfection programs.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires a clean and sanitary healthcare environment to maximize the prevention of infection and communicable disease.15 Evidence-based cleaning protocols, such as those provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), should be followed. This means the use of EPA-registered healthcare-grade disinfectants. To ensure compliance of these requirements, CMS surveyors will be on the lookout for the following:

- Environmental surfaces are regularly cleaned and disinfected following an established schedule (e.g., at least daily),

- Spills and visibly contaminated surfaces are promptly cleaned and disinfected, and

- High-touch surfaces are cleaned and disinfected more frequently than minimal-touch surfaces.15

CMS further requires that disinfectants are used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions for use.15 When used correctly, EPA-registered disinfectants, including bleach products, can be expected to be safe when used as directed. In fact, following label direction is required by law.16 The responsible use of any disinfectant entails the following:

- People:

- Education and Training – Ensure that staff are adequately education and trained. Clorox Healthcare offers best-in-class education and training materials (see our HealthyClean™ Program as one example).

- Competency — no education and training is complete with competency assessment.

- Product:

- Perks of Ready-to-Use products:

- Safer

- No mixing required

- No risk of dilution error

- Saves time

- Contact Time:

- Consider using the shorter contact time for your bleach products when sporicidal activity is not necessary. For example, Clorox Healthcare® Spore10 Defense™ Cleaner Disinfectant has a contact time of 1 minute for most pathogens, 3 minutes for C. auris, and 5 minutes for C. diff. This product can be used at one minute when sporicidal kill is not needed (which is likely most of the time). Spore Defense can also be used through an electrostatic sprayer. This will go a long way with surface compatibility.

- Perks of Ready-to-Use products:

- Practice:

- Always follow the manufacturer’s directions for use.

- Adhere to evidence-based cleaning and disinfection protocols such as those provided by the CDC.

In conclusion, these past few years have shown us that the pathogens are playing to win. Emerging pathogens and MDROs are coming at faster than ever before but with few new treatment options on the horizon. The good news is that we have some great weapons in our arsenal. I, for one, will be keeping bleach on my team!

References

1. The Joint Commission. Environmental Infection Prevention: Guidance for Continuously Maintaining a Safe Patient Care and Survey-Ready Environment [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 23]. Available from https://store.jcrinc.com/assets/1/7/nexclean_environinfectionprevention_%28002%29.pdf.

2. Encyclopedia.com. Sodium Hypochlorite [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/biographies/benelux-history-biographies/sodium-hypochlorite.

3. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAI) – Environmental Cleaning Procedures [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/resource-limited/cleaning-procedures.html.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: How to make a 0.1% Chlorine Solution to Disinfect Surfaces in Healthcare Settings [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/global-covid-19/make-chlorine-solution.html.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 Special Report: COVID-19 US Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/covid19-impact-report-508.pdf.

6. ContagionLive Infectious Disease Today. Containing an Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumanii in a COVID-19 Isolation Unit [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 29]. Available from https://www.contagionlive.com/view/containing-outbreak-carbapenem-resistant-acinetobacter-baumannii-covid-19-isolation-unit.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/cleaning/hospitals.html.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Summary of HAIs in the US: Assessing Progress 2006-2016 [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/archive/data-summary-assessing-progress.html.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Impact on HAIs in 2021 [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/covid-impact-hai.html#:~:text=First%20quarter%20standardized%20infection%20ratios,hospitalizations%20to%20all%2Dtime%20highs.

10. Fu Y, Luo Y, Grinspan A. Epidemiology of community-acquired and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8141977/.

11. Schelenz S, Ferry H, Rhodes J, Abdolrasouli A, Chowdhary A, Hall A. First Hospital Outbreak of the Globally Emerging Candida auris in a European Hospital. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2016;5:35.

12. Austin L, Guild P, Rovinski C, Osman J. Brief Report: Novel Case of C. auris in the VHA and in the state of South Carolina. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(11): 1258-1262.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Prevention and Control for Candida auris [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-infection-control.html.

14. Suleyman G, Alangaden G, Bardossy A. The Role of Environmental Contamination in the Transmission of Nosocomial Pathogens and Healthcare-Associated Infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018;20(6):12.

15. U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. Guidance Portal: Hospital Infection Control Worksheet [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 23]. Available from https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/document/hospital-infection-control-worksheet.

16. United States Environmental Protective Agency. About Pesticide Registration [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/about-pesticide-registration.

Appendix A

Range of bleach products offered by Clorox Healthcare to address different needs:

- Clorox Healthcare® Bleach Germicidal Disinfectant maintains fast disinfection efficacy while improving surface compatibility and residue profile to meet the needs of a changing healthcare environment. Built to kill nearly 60 microorganisms in 3 minutes or less, including C. diff and C. auris, these cleaners are ready to use and proven to be effective in the battle against HAIs.

- Clorox Fuzion® Cleaner Disinfectant uses a revolutionary technology to eliminate the chemical reaction that can damage surfaces and leave a residue. The solution contains sodium hypochlorite and a neutralizer that, when combined, form hypochlorous acid. The result is a highly effective disinfectant with broad surface compatibility and little to no residue. Fuzion® kills 53 microorganisms in two minutes or less, with a two-minute kill time on C. diff spores.

- Clorox Healthcare® Spore Defense™ Cleaner Disinfectant kills C. diff in 5 minutes, C. auris in 3 minutes, and 45 additional bacteria and viruses in 1 minute. The patented light bleach formula balances the need for strong efficacy with safety by using low levels of bleach, anti-corrosion ingredients and lower pH levels to ensure safety for surfaces and users facility-wide, and can be used through electrostatic devices.

Appendix B

The use of bleach on surfaces to address HO-CDI and surface contamination.

| Study | Results |

|---|---|

| Louh IK, Greendyke WG, Hermann EA, et al. Clostridium difficile Infection in Acute Care Hospitals: Systematic Review and Best Practices for Prevention. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 2017; 38(4):476-482. | Twice daily disinfection of high-touch surfaces and terminal cleaning of patient rooms with chlorine-based products in conjunction with auditing were found to be the most effective interventions, resulting in a 45% to 85% reduction in HO-CDI C. difficile infections. |

| Ng Wong YK, Alhmidi H, Mana TSC, Cadnum JL, Jencson AL, Donskey CJ. Impact of routine use of a spray formulation of bleach on Clostridium difficile spore contamination in non-C difficile infection rooms. American Journal of Infection Control, 2019 Jan 31. pii: S0196-6553(18)31205-7 | Routine use of Clorox Healthcare® Fuzion™ Cleaner Disinfectant, a spray formulation of bleach, in non-C. difficile infection rooms was found to reduce C. difficile spore contamination. |

| Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE, Fedraw LA. A Targeted Strategy to Wipe Out Clostridium difficile.” Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2011; 32(11):1137–1139. | Implementation of a bundle of interventions that included daily and discharge cleaning with Clorox Healthcare® Germicidal Wipes resulted in an 85% decrease in HO-CDI rate. |

| Abbett SK, Yokoe DS, Lipsitz SR, Bader AM, Berry WR, Tamplin EM, Gawande AA. Proposed Checklist of Hospital Interventions to Decrease the Incidence of Healthcare-Associated Clostridium difficile Infection. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2009; 30(11):1062–1069. | Implementation of a three-part bundle that included the use of a ready-to-use bleach disinfecting solution on surfaces led to a 40% reduction that was sustained for 21 months. |

| Mayfield, JL, et al. Environmental Control to Reduce Transmission of Clostridium difficile. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2000; 31(4):995–1000. | Implementation of an infection control bundle that included routine bleach cleaning of surfaces resulted in a 61% decrease in the rate of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. |

| Mullen KM, et al. “Use of Hypochlorite Solution to Decrease Rates of Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea.” Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 2007; 28(2):205–207. | Implementation of bleach cleaning protocols as part of a multifaceted approach was associated with an almost 80% decrease in C. difficile-associated diarrhea incidence rates. |

| Mermel LA, Jefferson J, Blanchard K, Parenteau S, Mathis B, Chapin K, Machan JT. Reducing Clostridium difficile Incidence, Colectomies, and Mortality in the Hospital Setting: A Successful Multidisciplinary Approach. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2013; 39(7): 298-305. | C. difficile infection rates and associated mortality were decreased following the implementation of a series of multidisciplinary interventions, including enhanced environmental disinfection with Dispatch® Hospital Cleaner Disinfectant with Bleach. |

| Koll BS, Ruiz RE, Calfee DP, Jalon HS, Stricof RL, Adams A, Smith BA, Shin G, Gase K, Woods MK, Sirtalan I. Prevention of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection in the New York metropolitan region using a collaborative intervention model. Journal of Healthcare Quality, 2014; 36(3):35-45. | A collaborative multifaceted approach to prevent C. difficile infection resulted in a significant reduction in the mean HO-CDI rate and up to $6.8 million in cost savings. |