Introduction

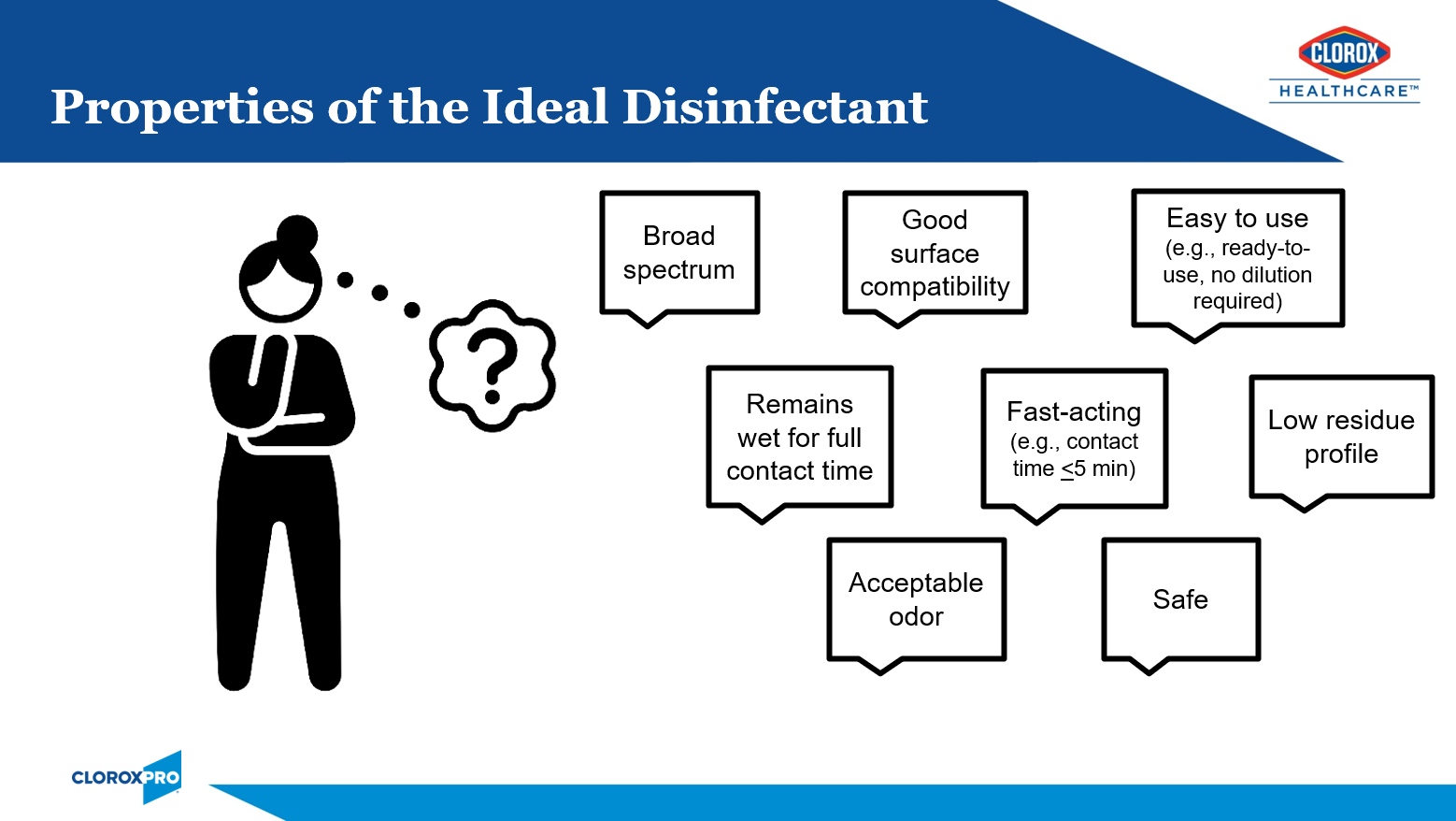

Healthcare facilities have many options when it comes to surface disinfectant selection. While no one product checks off all of the boxes of the ideal disinfectant (Figure 1), I will share why I think bleach is B.E.S.T. in this article. I will start with a brief history of bleach, tackling tough pathogens, responsible bleach use, and the critical moments for bleach use.

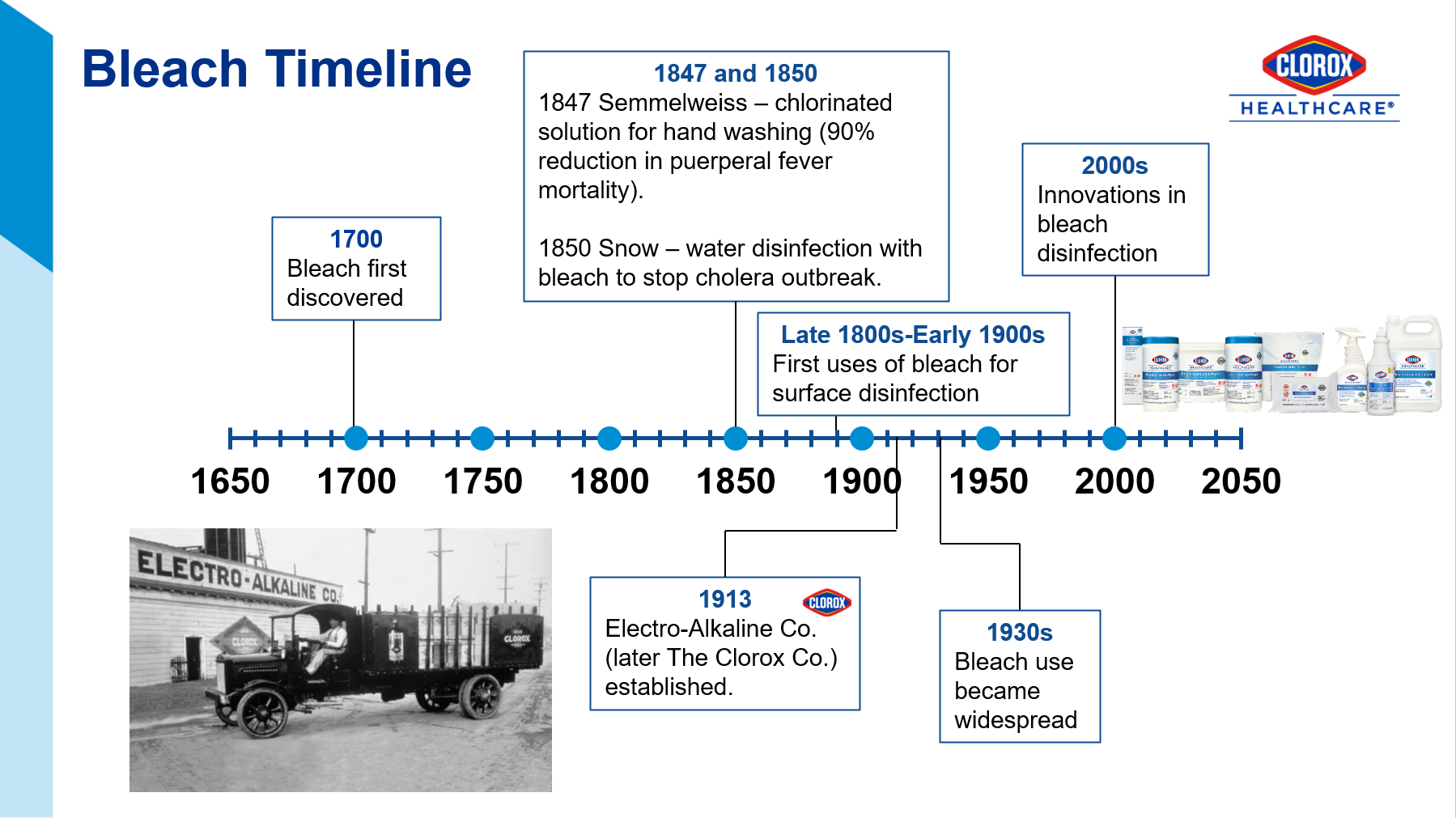

The Joint Commission recommends that healthcare facilities limit the number of disinfectants to 2-3 products with at least one having a sporicidal claim, like bleach.1 Sodium hypochlorite (the active ingredient in bleach), has withstood the test of time since its discovery in the late 1700s (Figure 2)2. This is because it is relatively inexpensive, readily available, and has efficacy against a broad range of pathogens.

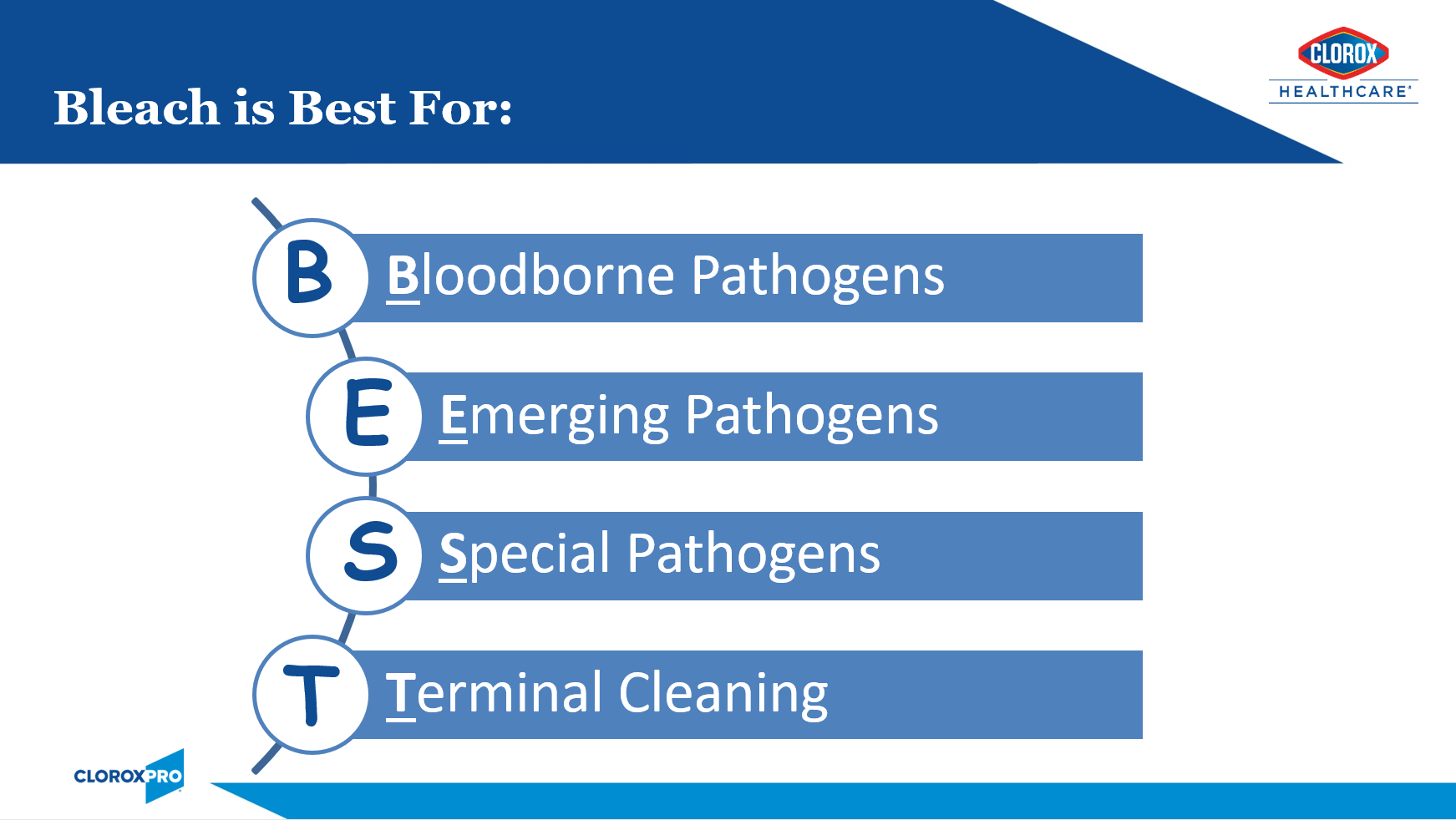

B.E.S.T. Use Indications for Bleach

Innovative chemists have developed lower-level sodium hypochlorite products that offer good surface compatibility, low odor, and acceptable contact times while still being sporicidal. Our compatibility program has endorsements from key equipment manufacturers. See Appendix A for a range of bleach products to address different needs. While these improved bleach formulations are gentle enough for everyday use, shared here are some of the most critical moments for its use. The mnemonic B.E.S.T. will help you to remember these key moments (Figure 3).

- Bloodborne Pathogens:

- For cleaning and disinfection of blood or body fluid spills, the CDC recommends a 1:100 (small spills) or 1:10 dilution (large spills) of 5% bleach.3 The EPA Master Label for pre-diluted ready-to-use bleach-based disinfectants should provide information on the products dilution ratio.

- Emerging and Re-emerging Pathogens:

- Bleach is often the go-to disinfectant active for emerging or re-emerging pathogens. Examples include:

- COVID-19: While products with the EPA-approved emerging viral pathogen claim (List N) are expected to kill SARS-CoV-2, there were supply chain issues during the pandemic. Bleach to the rescue! Many facilities relied on “jug” bleach diluted in accordance with CDC recommendations.4

- Novel Influenza strains: I specifically recall the H1N1 pandemic of 2009. Since this was before the EPA had implemented their Emerging Viral Pathogens policy, the CDC had recommended use of bleach until more was learned about killing this viral strain.

- Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumanii (CRAB): According to CDC special report earlier this year, the incidence of CRAB increased 78% during the pandemic.5 This problematic emerging pathogen is difficult to eradicate due to its ability to survive for prolonged periods in the environment. The CDC recommends enhanced cleaning and disinfection. A recent of outbreak of CRAB in a South Korea hospital was eventually contained when twice daily disinfection with bleach was implemented.6

- Ebola: While historical Ebola outbreaks have mostly been contained to the African continent, the current outbreak in Uganda, again raises concerns for imported cases. Emergency preparedness means having appropriate products on-hand. The CDC recommends the use of an EPA-registered hospital disinfectant from List L.7 I am particularly proud of the fact that the Clorox Company is the only disinfectant manufacturer with EPA-registered label claims against the Ebola virus.

- The above examples are all viral. Please note that the EPA Emerging Viral Pathogens Policy only applies to viruses. It will not apply should the next emerging pathogen be a bacterial or fungal in nature. For this reason, it’s a great idea to ensure that you always have bleach on-hand.

- For additional reassurance against these troublesome pathogens, consider use of adjunct disinfection such as electrostatic technology to ensure that all surfaces and nooks and crannies are covered. You will need to ensure that the product is EPA-approved for use through electrostatic sprayers.

- Bleach is often the go-to disinfectant active for emerging or re-emerging pathogens. Examples include:

- Special Pathogens — Two of the most troublesome pathogens that call for enhanced infection control measures to control their spread, are outlined here:

- Clostridiodes difficile (C. diff):

- C. diff remains one of the most common causes of healthcare-associated infections.8 The hardy spores can persist in the environment for many months and are very difficult to kill (see Figure 3 above). These spores can be picked up on the hands of healthcare workers and transmitted to other patients. Until recently, bleach was the only sporicidal disinfectant available to kill C. diff spores. With the use of bleach and other infection prevention efforts, the HO-CDI standardized infection ratio (SIR) has decreased from 0.85 in 2016 to 0.48 in 2021.8,9 There is an abundance of studies demonstrating the effectiveness of bleach in reducing HO-CDI rates (Appendix B). While we have made recent strides in reducing HO-CDI rates (hooray bleach!), we must remain vigilant as community-acquired C. diff incidence is on the rise.10 As these patients seek medical attention, the pathogen can get re-introduced into our facilities. Click here for a great C. diff Terminal Cleaning Protocol & Checklist.

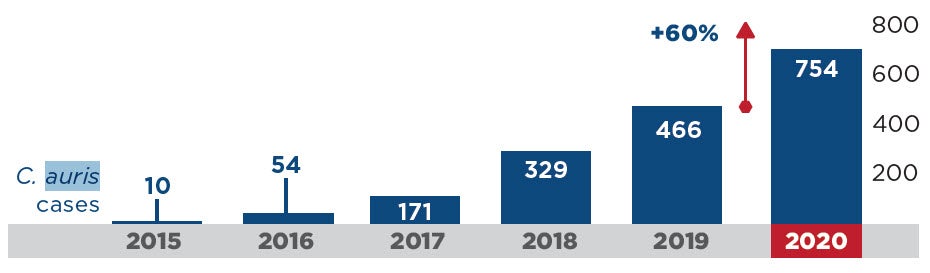

- Candida auris (C. auris):

- This emerging threat is a very worrisome multidrug-resistant yeast with a mortality rate between 30-60%. During the pandemic, HAIs caused by C. auris increased an alarming 60% (Figure 4).5 Because this pathogen is transmitted by the contact (or touch) route and because it persists in the environment for prolonged periods, it spreads rapidly in healthcare settings. It can be very difficult to eradicate and outbreaks often result. Several outbreaks documented in the literature reported enhanced cleaning and disinfection with bleach successfully contained the outbreak.11,12 In fact, the CDC recommends using an EPA-registered hospital-grade disinfectant effective against C. auris or C. diff spores, including bleach.13 Click here to learn more from my C. auris webinar (free CE’s!).

- Clostridiodes difficile (C. diff):

COVID-19 Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance in the U.S.

- Terminal Cleaning:

- Several studies have shown that patients admitted to rooms previously occupied by individuals infected or colonized with MDROs or C. diff are at up to three times higher risk of acquiring these pathogens.14 CMS requires that after a patient vacates a room, all visibly or potentially contaminated surfaces are thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.15 Each patient deserve the highest level of surface cleaning and disinfection, therefore I recommend, at a minimum, using a bleach-based cleaner-disinfectant for all discharge and isolation cleanings.

Responsible Bleach Use

After nearly 3 years of dealing with pandemic, including staffing and supply chain issues, practices may have drifted from our written protocols. For example, are staff being compliant with bleach use when it’s indicated? It’s now time that we reassess our cleaning and disinfection programs.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires a clean and sanitary healthcare environment to maximize the prevention of infection and communicable disease.15 Evidence-based cleaning protocols, such as those provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), should be followed. This means the use of EPA-registered healthcare-grade disinfectants. To ensure compliance of these requirements, CMS surveyors will be on the lookout for the following:

- Environmental surfaces are regularly cleaned and disinfected following an established schedule (e.g., at least daily),

- Spills and visibly contaminated surfaces are promptly cleaned and disinfected, and

- High-touch surfaces are cleaned and disinfected more frequently than minimal-touch surfaces.15

CMS further requires that disinfectants are used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions for use.15 When used correctly, EPA-registered disinfectants, including bleach products, can be expected to be safe when used as directed. In fact, following label direction is required by law.16 The responsible use of any disinfectant entails the following:

- People:

- Education and Training – Ensure that staff are adequately education and trained. Clorox Healthcare offers best-in-class education and training materials (see our HealthyClean™ Program as one example).

- Competency — no education and training is complete with competency assessment.

- Product:

- Perks of Ready-to-Use products:

- Safer

- No mixing required

- No risk of dilution error

- Saves time

- Contact Time:

- Consider using the shorter contact time for your bleach products when sporicidal activity is not necessary. For example, Clorox Healthcare® Spore10 Defense™ Cleaner Disinfectant has a contact time of 1 minute for most pathogens, 3 minutes for C. auris, and 5 minutes for C. diff. This product can be used at one minute when sporicidal kill is not needed (which is likely most of the time). Spore Defense can also be used through an electrostatic sprayer. This will go a long way with surface compatibility.

- Perks of Ready-to-Use products:

- Practice:

- Always follow the manufacturer’s directions for use.

- Adhere to evidence-based cleaning and disinfection protocols such as those provided by the CDC.

In conclusion, these past few years have shown us that the pathogens are playing to win. Emerging pathogens and MDROs are coming at faster than ever before but with few new treatment options on the horizon. The good news is that we have some great weapons in our arsenal. I, for one, will be keeping bleach on my team!

References

1. The Joint Commission. Environmental Infection Prevention: Guidance for Continuously Maintaining a Safe Patient Care and Survey-Ready Environment [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 23]. Available from https://store.jcrinc.com/assets/1/7/nexclean_environinfectionprevention_%28002%29.pdf.

2. Encyclopedia.com. Sodium Hypochlorite [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from https://www.encyclopedia.com/history/biographies/benelux-history-biographies/sodium-hypochlorite.

3. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAI) – Environmental Cleaning Procedures [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/prevent/resource-limited/cleaning-procedures.html.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19: How to make a 0.1% Chlorine Solution to Disinfect Surfaces in Healthcare Settings [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/global-covid-19/make-chlorine-solution.html.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022 Special Report: COVID-19 US Impact on Antimicrobial Resistance [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/covid19-impact-report-508.pdf.

6. ContagionLive Infectious Disease Today. Containing an Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumanii in a COVID-19 Isolation Unit [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 29]. Available from https://www.contagionlive.com/view/containing-outbreak-carbapenem-resistant-acinetobacter-baumannii-covid-19-isolation-unit.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Guidance for Environmental Infection Control in Hospitals for Ebola Virus [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 18]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/clinicians/cleaning/hospitals.html.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Summary of HAIs in the US: Assessing Progress 2006-2016 [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/archive/data-summary-assessing-progress.html.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Impact on HAIs in 2021 [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 17]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/hai/data/portal/covid-impact-hai.html#:~:text=First%20quarter%20standardized%20infection%20ratios,hospitalizations%20to%20all%2Dtime%20highs.

10. Fu Y, Luo Y, Grinspan A. Epidemiology of community-acquired and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021. Available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8141977/.

11. Schelenz S, Ferry H, Rhodes J, Abdolrasouli A, Chowdhary A, Hall A. First Hospital Outbreak of the Globally Emerging Candida auris in a European Hospital. Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control. 2016;5:35.

12. Austin L, Guild P, Rovinski C, Osman J. Brief Report: Novel Case of C. auris in the VHA and in the state of South Carolina. Am J Infect Control. 2022;50(11): 1258-1262.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Infection Prevention and Control for Candida auris [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from https://www.cdc.gov/fungal/candida-auris/c-auris-infection-control.html.

14. Suleyman G, Alangaden G, Bardossy A. The Role of Environmental Contamination in the Transmission of Nosocomial Pathogens and Healthcare-Associated Infections. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2018;20(6):12.

15. U.S. Dept. of Health & Human Services. Guidance Portal: Hospital Infection Control Worksheet [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 23]. Available from https://www.hhs.gov/guidance/document/hospital-infection-control-worksheet.

16. United States Environmental Protective Agency. About Pesticide Registration [Internet]. [Cited 2022 Oct 21]. Available from https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/about-pesticide-registration.

Appendix A

Range of bleach products offered by Clorox Healthcare to address different needs:

- Clorox Healthcare® Bleach Germicidal Disinfectant maintains fast disinfection efficacy while improving surface compatibility and residue profile to meet the needs of a changing healthcare environment. Built to kill nearly 60 microorganisms in 3 minutes or less, including C. diff and C. auris, these cleaners are ready to use and proven to be effective in the battle against HAIs.

- Clorox Fuzion® Cleaner Disinfectant uses a revolutionary technology to eliminate the chemical reaction that can damage surfaces and leave a residue. The solution contains sodium hypochlorite and a neutralizer that, when combined, form hypochlorous acid. The result is a highly effective disinfectant with broad surface compatibility and little to no residue. Fuzion® kills 53 microorganisms in two minutes or less, with a two-minute kill time on C. diff spores.

- Clorox Healthcare® Spore Defense™ Cleaner Disinfectant kills C. diff in 5 minutes, C. auris in 3 minutes, and 45 additional bacteria and viruses in 1 minute. The patented light bleach formula balances the need for strong efficacy with safety by using low levels of bleach, anti-corrosion ingredients and lower pH levels to ensure safety for surfaces and users facility-wide, and can be used through electrostatic devices.

Appendix B

The use of bleach on surfaces to address HO-CDI and surface contamination.

| Study | Results |

|---|---|

| Louh IK, Greendyke WG, Hermann EA, et al. Clostridium difficile Infection in Acute Care Hospitals: Systematic Review and Best Practices for Prevention. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 2017; 38(4):476-482. | Twice daily disinfection of high-touch surfaces and terminal cleaning of patient rooms with chlorine-based products in conjunction with auditing were found to be the most effective interventions, resulting in a 45% to 85% reduction in HO-CDI C. difficile infections. |

| Ng Wong YK, Alhmidi H, Mana TSC, Cadnum JL, Jencson AL, Donskey CJ. Impact of routine use of a spray formulation of bleach on Clostridium difficile spore contamination in non-C difficile infection rooms. American Journal of Infection Control, 2019 Jan 31. pii: S0196-6553(18)31205-7 | Routine use of Clorox Healthcare® Fuzion™ Cleaner Disinfectant, a spray formulation of bleach, in non-C. difficile infection rooms was found to reduce C. difficile spore contamination. |

| Orenstein R, Aronhalt KC, McManus JE, Fedraw LA. A Targeted Strategy to Wipe Out Clostridium difficile.” Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2011; 32(11):1137–1139. | Implementation of a bundle of interventions that included daily and discharge cleaning with Clorox Healthcare® Germicidal Wipes resulted in an 85% decrease in HO-CDI rate. |

| Abbett SK, Yokoe DS, Lipsitz SR, Bader AM, Berry WR, Tamplin EM, Gawande AA. Proposed Checklist of Hospital Interventions to Decrease the Incidence of Healthcare-Associated Clostridium difficile Infection. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2009; 30(11):1062–1069. | Implementation of a three-part bundle that included the use of a ready-to-use bleach disinfecting solution on surfaces led to a 40% reduction that was sustained for 21 months. |

| Mayfield, JL, et al. Environmental Control to Reduce Transmission of Clostridium difficile. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2000; 31(4):995–1000. | Implementation of an infection control bundle that included routine bleach cleaning of surfaces resulted in a 61% decrease in the rate of C. difficile-associated diarrhea. |

| Mullen KM, et al. “Use of Hypochlorite Solution to Decrease Rates of Clostridium difficile-Associated Diarrhea.” Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 2007; 28(2):205–207. | Implementation of bleach cleaning protocols as part of a multifaceted approach was associated with an almost 80% decrease in C. difficile-associated diarrhea incidence rates. |

| Mermel LA, Jefferson J, Blanchard K, Parenteau S, Mathis B, Chapin K, Machan JT. Reducing Clostridium difficile Incidence, Colectomies, and Mortality in the Hospital Setting: A Successful Multidisciplinary Approach. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2013; 39(7): 298-305. | C. difficile infection rates and associated mortality were decreased following the implementation of a series of multidisciplinary interventions, including enhanced environmental disinfection with Dispatch® Hospital Cleaner Disinfectant with Bleach. |

| Koll BS, Ruiz RE, Calfee DP, Jalon HS, Stricof RL, Adams A, Smith BA, Shin G, Gase K, Woods MK, Sirtalan I. Prevention of hospital-onset Clostridium difficile infection in the New York metropolitan region using a collaborative intervention model. Journal of Healthcare Quality, 2014; 36(3):35-45. | A collaborative multifaceted approach to prevent C. difficile infection resulted in a significant reduction in the mean HO-CDI rate and up to $6.8 million in cost savings. |