Petri dishes and prisons; antiseptics and ventilation. The interests of Sir John Pringle.

This is the first of a series of historical blog posts, each of which will cover the life and work of infection control pioneers or celebrate key related events. This post features Sir John Pringle whose original ideas laid the foundation for aspects of infection control that we take for granted today.

On the first day of January 1750, the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society published three remarkable articles. The first, titled “Some experiments on substances resisting putrefaction” was followed by two others, both of which described additional experiments on the topic. The articles are notable because they describe the first scientific study on these substances which the author called “antiseptics”, and they represent one of the earliest uses of the word “antiseptic”, a term which some have attributed to the author.

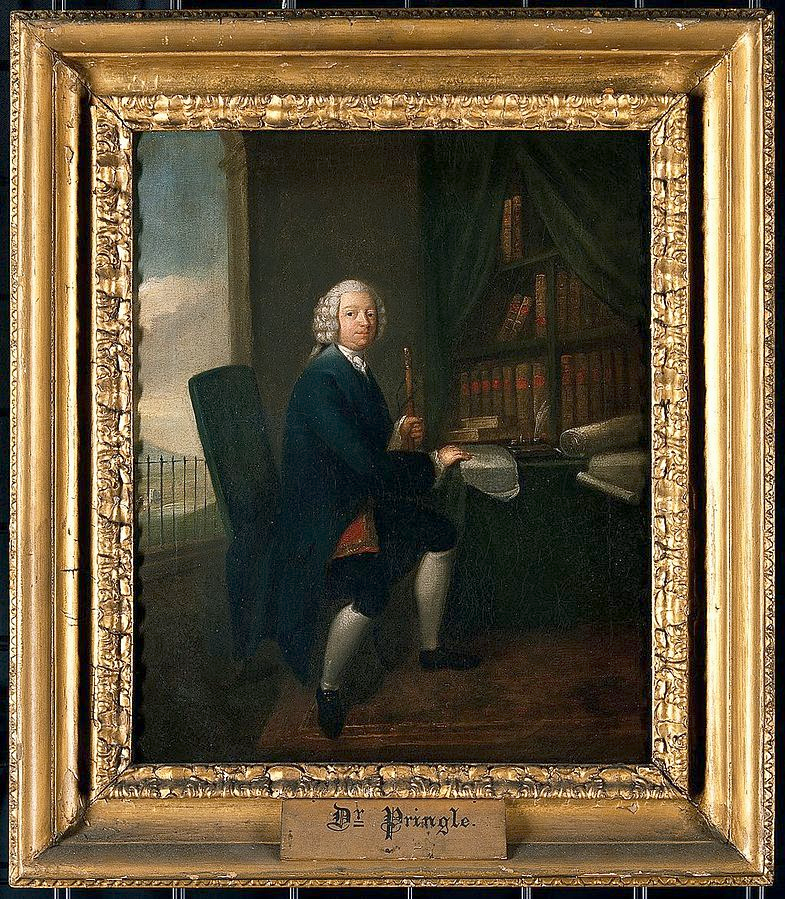

That author was Sir John Pringle. Readers of Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology (ICHE) may well be familiar with him, as his portrait has graced the front cover of every volume in 2020. He sits at a desk facing the unknown artist, looking as if he’s been interrupted while reading a manuscript, and holds a walking stick in his left hand. He wears the typical dress of a gentleman of his time; black breeches falling just below the knee, white stockings, a long, dark coat, and a fashionable silvery-gray wig. The journal gives a brief description of his achievements but there’s much more to Sir John, physician to the army and the Royal Family, President of the Royal Society, and one of the pre-eminent physicians of his day.

Sir John, it turns out, was far ahead of his time. His pioneering work on antiseptics, combined with his work on his constant aim of “preventing infection, the common and fatal consequence of a large and crowded hospital” perhaps entitles him to be considered not just a founding father of military medicine, but as a pioneer of public health and infection prevention practices.

His experiences on the battlefields during the War of the Austrian Succession in the 1740’s appears to have shaped much of his thinking around transmission and prevention of infectious diseases. His most important work, Observations on the Diseases of the Army, published in 1750 gave, for the first time, a scientific account of the epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention of hospital cross-infections. He observed that military hospitals with their poor ventilation, unsanitary conditions and overcrowding were a chief cause of sickness and death, citing for instance, the spread of dysentery between patients in the same wards through infectious straw probably used as bedding.

He also recognized that outbreaks of jail fever and hospital fever were the same disease – typhus, reaching this conclusion after observing that deserters with jail fever transmitted the disease to English troops, who then became the source of hospital fever outbreaks. His advice for prevention of flea and lice-spread typhus is as sound today as it was then; burn the clothes of prisoners and executed criminals and give new clothes to prisoners and wash them from time to time. Furthermore, these observations led him to describe interventions to moderate or prevent the contagion including dispersing the sick, preserving pure air in the wards, reducing overcrowding, along with other hygienic measures to combat sepsis.

That idea that pure air could help prevent the spread of infection became apparent in October 1750. After an outbreak of jail fever in Newgate Prison and the law courts of the Old Bailey (the latter had taken the life of the Lord Mayor of London), Sir John joined a committee to investigate. It had a clear objective:

“to inquire into the best means for procuring in Newgate such a purity of air, as might prevent the rise of those infectious distempers, which not only had been destructive to the prisoners themselves, but dangerous to others, who had any communication with them”.

A Royal Society publication of 1753 describes the investigation and the solution which was the installation of a windmill-powered ventilator invented by the leading ventilation expert of the time, the Reverend Dr. Stephen Hales. This device “sweetened” the air in the building by drawing out the foul air from the lower stories to the upper. After installation, deaths in the prison decreased from eight a week to about two a month, but not until seven of the workmen installing the device died of the fever. Two hundred and seventy years later, the importance of good ventilation to help prevent the spread of COVID-19 is becoming very clear.

But back to antiseptics, and a connection to modern day disinfectants. The Royal Society publications describe in meticulous detail, Sir John’s controlled experiments on a range of exotic-sounding substances. His method was simple – add the substance to a small piece of meat in water, cap the tube and keep it warm, then observe whether the meat putrefied or not. Substances that prevented or stopped putrefaction he called “antiseptic”. What the substances were doing was killing or preventing the growth of bacteria that would cause putrefaction.

At this point, it’s worth remembering that although van Leeuwenhoek had observed bacteria through his microscope in 1676, they were virtually ignored for over 100 years and not well known at the time of Sir John’s experiments. In fact, nowhere in the three publications does the word “bacteria” appear.

Of the countless exotic-sounding and common substances tested, he found that alkalis as Spirit of Hartshorn (aqueous ammonia solution derived from the horns of a male red deer) and salammoniac (ammonium chloride) and acids such as vinegar (acetic acid) and lemon juice (citric acid) were effective antiseptics. This is perhaps not surprising to the modern reader with a basic knowledge of antimicrobial mechanism of action. For these substances, or derivatives of them form the basis of many disinfectants today; quaternary ammonium chlorides are essentially ammonium salts; acetic acid when combined with hydrogen peroxide forms peracetic acid, an especially powerful antimicrobial agent. And citric acid is finding its place as an EPA-approved Safer Choice active antimicrobial ingredient.

We have a lot to thank Sir John Pringle for; basic infection prevention measures for hospitals, the idea of fresh air and good hygiene, fundamental research into antiseptics. Well-thought of in his time – there is even a memorial to him in Westminster Abbey – his contributions seem to have been forgotten over time. Thanks to ICHE for bringing him to life in 2020. I’m eagerly waiting to see who’s on the front cover in 2021.