Norovirus: The Most Common Unknown Pathogen to Cause Infections

Norovirus. You might not know it by name, but you’ve definitely heard about it before. News headlines go something like this, “School closes due to large sudden outbreak, many students and staff sick,” or “Dozens sick after meal at favorite local restaurant.” While the news references “food poisoning,” “gastroenteritis” or even the “stomach flu,” the truth is norovirus isn’t really the flu at all.

For those of us who monitor infectious disease outbreak news daily, the culprit at play in these situations can be fairly obvious. This is because norovirus has a unique way of making people sick compared to other germs. Main symptoms of a norovirus infection include diarrhea and vomiting, and ingesting very little (as few as 10 viral particles) is required to make someone sick. This is why norovirus spreads so easily, especially in busy, enclosed environments such as schools and daycare centers, and why so many people can get sick at once. Additionally, norovirus spreads easily by contaminated hands when restaurant and healthcare employees aren’t diligent about hygiene.

Why is norovirus a concern?

Simply said, norovirus is a concern because it causes a lot of illness both domestically and globally, and can even cause death.

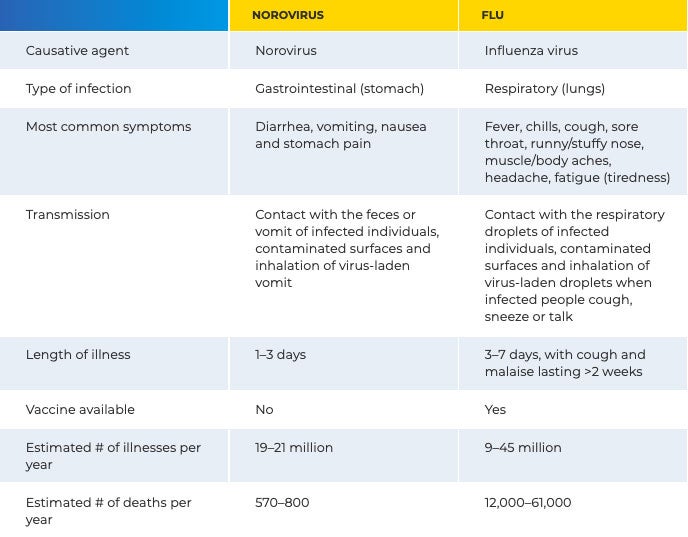

In the U.S., norovirus is the leading cause of vomiting and diarrhea. It is responsible for 19 million to 21 million illnesses each year. Almost two million people seek outpatient treatment, and a further 400,000 seek treatment at hospital emergency rooms. Annually, 56,000–71,000 people are hospitalized, and approximately 570–800 die.1 There is no vaccine for norovirus, and because there are many types of norovirus and it mutates quickly, you can get it multiple times in your lifetime.

Furthermore, between 2009 and 2012, almost 3,500 norovirus outbreaks were reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Outbreak Reporting System. Of those, 63% were in healthcare settings, with the overwhelming majority of those outbreaks occurring in long-term care facilities and nursing homes. Restaurants and banqueting facilities accounted for 22% of the outbreaks, while 6% occurred in schools.2 While norovirus is the cause for most of the diarrheal outbreaks on cruise ships, cruise ships account for only 1% of reported norovirus outbreaks.4 From August through December 2019, there were 285 norovirus outbreaks reported to the CDC’s NoroSTAT network, a norovirus surveillance and tracking collaborative.3

How do you know if you have norovirus?

As mentioned, norovirus illness shows up in a unique way so it can be easily identified if you know what to look for.

- The symptoms are the first clue. The most common symptoms of norovirus are diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and stomach pain.

- Secondly, a person usually develops symptoms 12–48 hours after being exposed to norovirus.4 While it may be difficult to know when the first person in a facility was exposed to the virus, there are usually a number of “close-contacts” that will become sick with the same symptoms within the 12–48 hour time frame. This is a tell-tale sign of norovirus: waves of people get sick approximately every 12–48 hours.

- Finally, norovirus illness is short-lived, and for most people only lasts for a 1–3 days.

Additionally, since norovirus and the flu are often confused with one another — as they are both illnesses that spike in the winter months — here is a quick “cheat sheet” of the differences:

How can norovirus be prevented?

Vaccines are the number one way to prevent most infectious diseases, but since a vaccine is not yet available for norovirus, other prevention measures are critical. The best ways to help prevent norovirus from impacting a facility are:

- Practice excellent hand hygiene. Everyone should be carefully washing their hands with soap and water, especially after using the toilet and changing diapers, and always before eating or preparing food.

- Safely handle and prepare food and DO NOT let anyone prepare food or care for others if they are sick. Fruits and vegetables should be washed and seafood cooked thoroughly before serving and eating. Sick food service employees in restaurants, schools, daycares and long-term care facilities should not return to work until at least two days after symptoms, such as diarrhea, stop.

- Regularly and properly clean and disinfect surfaces. Ensure the use of proper cleaning techniques and best practices (e.g., clean to dirty, top to bottom, color coded cloths) and follow label instructions for ready-to-use EPA-registered cleaner disinfectants with efficacy claims against norovirus. Surfaces should stay wet for the contact time listed on product labels, and disposable cleaning cloths should be used, unless using pre-moistened disinfecting wipes. Clean and disinfect all touchable surfaces daily, especially in busy facilities where immunocompromised individuals may be present, such as hospitals, schools, daycares, oncology and dialysis clinics, and long-term care centers.

How to contain a norovirus infection?

If you or someone in your building has been infected with norovirus, the best thing to do is follow the same prevention practices above, which will help to contain the spread. You can also adopt these additional best practices for up to two weeks after the last person has been sick, which is the amount of time it takes for some people to stop shedding the virus in their stool.

- Wear appropriate protection. ServSafe®, the ANSI-accredited National Restaurant Association’s food safety and certification program, recommends that before cleaning up an area where vomiting and diarrhea has taken place, employees should don disposable masks, nonabsorbent disposable gloves, eye protection and aprons.5

In healthcare settings, patients with suspected norovirus should be placed on standard and contact precautions for a minimum of 48 hours after the resolution of symptoms. This means that for anyone entering the area of a norovirus patient should at minimum wear gloves and a gown. - Wash laundry with precaution. If an item has been contaminated with feces or vomit from someone with norovirus infection and cannot be disposed of, wear gloves and take care not to agitate it too much before placing it in the laundry. Run the washer and dryers on their longest cycles, consider using a laundry sanitizer or disinfectant as an additive, and wash hands thoroughly and immediately after handling a contaminated load. It’s also a good practice to wipe down all touched surfaces with an EPA-registered disinfectant effective against norovirus.

- Increase the frequency of cleaning and disinfecting touchable surfaces. In healthcare settings, the CDC recommends that cleaning and disinfecting should be performed twice daily, with frequently touched surfaces cleaned and disinfected three times daily.6 Following a similar recommendation for non-healthcare facilities is also warranted if norovirus is suspected or confirmed.

For more information on norovirus, visit the CDC website or refer to our Norovirus Education Sheet.

References:

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Norovirus Outbreaks. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/norovirus/index.html Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR. Vital Signs: Foodborne Norovirus Outbreaks — United States, 2009–2012 https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6322a3.htm Accessed Dec 11, 2019.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NoroSTAT Data. www.cdc.gov/norovirus/reporting/norostat/index.html Accessed Jan 31, 2020.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Symptoms of Norovirus. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/about/symptoms.html Accessed Jan 31, 2020.

5. ServeSafe National Restaurant Association. Norovirus: The Notorious Dangers. https://www.servsafe.com/media/ServSafe/Products/Norovirus/Norovirus-The-Notorious-Dangers-Whitepages-(Final).pdf Accessed Jan 31, 2020.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Norovirus in Healthcare Facilities Fact Sheet. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/norovirus/229110-ANoroCaseFactSheet508.pdf Accessed Jan 31, 2020.